Beauty and the brain: The science of neuroaesthetics

What goes on in our brains when we encounter beauty? And what can neuroscience offer to help us understand the aesthetic impact of not only art but also science?

To answer these questions, I spoke with Dr. Anjan Chatterjee, who is a pioneer in the field of neuroaesthetics. He is Professor of Neurology, Psychology, and Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania and the founding director of the Penn Center for Neuroaesthetics.

Anjan’s clinical practice focuses on patients with cognitive disorders, and his research addresses neuroaesthetics, spatial cognition, language, and neuroethics. He is author of The Aesthetic Brain: How We Evolved to Desire Beauty and Enjoy Art, as well as co-editor of a brand-new volume, Brain, Beauty, and Art, as well as a co-editor of two other books — one on neuroethics, and one on cognitive neuroscience.

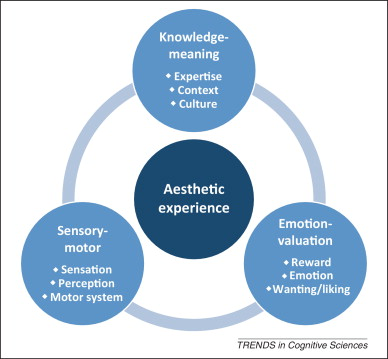

In our interview, we discuss what he has learned about the impact of beauty on the brain from his decades of research. We explore his model of the “aesthetic triad,” which understands aesthetic experience as an emergent property of three interrelated systems in the brain: sensory-motor, emotion-valuation, and knowledge-meaning.

We also discuss the many ways in which culture shapes the relationship between our aesthetic and moral judgments—sometimes in very detrimental ways, such as when we judge people with facial deformities as morally suspect. And we discuss what the science of beauty can tell us about the beauty of science.

You can download the podcast episode below wherever you usually get your podcasts:

iOS | Android | Spotify | RSS | Amazon | Stitcher | Podvine

You can also check out a video of our interview on YouTube.

A transcript of our conversation follows.

Brandon: Thank you so much for joining us today. I’m especially thrilled to have you here, because you're one of the few people I know who could talk about both the science of beauty and the beauty of science. So, welcome!

Anjan: Brandon, thank you very much for inviting me to talk about this topic, which is near and dear to my heart.

Brandon: Great. Well, to get started, tell us what drew you to studying the brain, especially after a BA in Philosophy.

Anjan: Well, the trajectory was, when I graduated from college, the question was whether to go to philosophy graduate school or go into medicine. The reason for medicine was I was familiar. My father was a physician. My mother was a nurse. My sister is a scientist. So, it's all familiar territory.

I ended up thinking that philosophy, which completely bewildered my parents that I wanted to study this in college. But I thought I would not be a very good philosopher unless I had some empirical grounding. So, that was really the main reason why I ended up going into medicine. By a circuitous route, one which I would not have predicted, I ended up studying, as you can imagine, ideas that are prominent in philosophy — philosophy of mind, philosophy of aesthetics through a biological lens.

Brandon: Okay. So then, the pathway from medical school to neuroaesthetics, how did that come about? Were you always interested in art or aesthetics? Was that something that emerged as a result of your studies in neurology? How did that come about?

Anjan: In medical school, and this relates to your first question, I found that once we got to the neuroscience section — we used a classic textbook that is still in use in a much later edition, written by Kandel and Schwartz at the time. I found that I was reading the text purely for the desire to know the information, as opposed to in order to answer, do well on tests, and that sort of thing — which was the first sign that neuroscience might be something that would capture my imagination.

I decided, once I was in the clinic, that the phenomenology of people who had different kinds of brain damage, the phenomenology of what was happening to their thinking, what we could infer about the state of their consciousness was the most interesting and amazing thing that I had experienced. That this could be a vehicle to understand how our minds work was very compelling.

Now, mind you, when I was in med school, this was in the early '80s. Most people thought this was academic suicide. To study cognition, it was too soft. It was too fuzzy. No self-respecting scientists would study this. If you were wanting to be taken seriously, you would be studying protein chemistry, or cellular biology, or even immunology, which I was in med school from '81 to '85. That was when AIDS first hit the scene. By the time I graduated, it was a pandemic or not a pandemic, but an epidemic.

There was all this interest in what's going on with our immune system that it can go so awry. This idea that you would study these questions about mind at the time were regarded as not — something maybe you talked about at cocktail parties, and you've made reference to Oliver Sacks. But no self-respecting scientist would actually make this their career. Nonetheless, it is what I found the most fascinating. At the time, there were only a few places where one could get added training in that. Because, again, the zeitgeist of it. So, that's what got me into studying this.

The specifics of aesthetics is a little more complicated because, at the time, there was no field of neuroaesthetics. Nobody was really studying that. So, I had been studying spatial attention. I've been studying language, as you mentioned, the relationship between space and language and how we communicate. But in the background, I had always been interested in aesthetics. I went to school in India. I went to a Jesuit school in India. One of our classes growing up was drawing every grid in the same way that you might have geography, and history, and math, and English. Drawing was one of the classes. So, I always drew.

I continued through med school, just having a sketch pad with me a lot of the time. Then things got very busy. Then I switched after residency. I switched to photography. So, this was always a pre-occupation. I always enjoyed being careful about the objects around me, picking things. I always felt like I had — this may sound peculiar — a relationship to inanimate objects. That relationship was predicated on an attachment that was also informed by the beauty of the object. So, I think that always preoccupied me.

In 1999, I moved to Penn back, when I was at the University of Alabama in Birmingham at that time. Penn was starting a center for cognitive neuroscience. It was a time to reflect on what I had been doing and what my research interests were. At the time, I thought that I had always been interested in aesthetics. If I didn't make that at least part of my research portfolio, I would regret that. So, that's how it started.

Around 1998, '99, there was literally nothing written about the topic. For some of your younger listeners, it may be peculiar. But I did what old school scholars did, which is I physically went to a library, and walked up and down the stacks to see what magazines even existed, the journals there were. Because we didn't have PDFs. We didn't have Google Scholar. But I found a couple of journals. That's how I saw what was going on, and became involved in an organization that does empirical aesthetics, which I think, as you know, we just had our meeting which we hosted in Philadelphia a few weeks ago. But back in the early 2002, it was the first meeting that I went to, which was in Japan. I found that there's a community of people who actually study this. So, that's how it all came about.

Brandon: Great. Tell me about, I guess, what the field of neuroaesthetics has taught us. I suppose, what do we gain? What insight do we gain about the nature of beauty from studying the brain? Are we hardwired for beauty in any sense? How would you see that?

Anjan: It's a great question. It's an important question, one that we ask every few months in my lab, which is what's the added value of putting the brain in the equation? We can study behavior very well. It turns out to be a very hard question to answer. Because very good behavioral studies often give you most of what you want to know. I think what the brain allows us to do is to look at it in a different way and to think about the systems and the principles by which our brains evolved and are organized, as a way of framing and putting some guardrails on how we even ask questions.

There are certain things that brain imaging can inform us about, which is the ways in which our brains might be responding to various objects and stimuli in the world in a way that we're not even aware that that's happening. On the other side, as a neurologist, the phenomenology of what happens to people when they have brain damage and how that might affect their artistic sensitivities or the way in which they produce art is another avenue by which we can start asking questions of the nature of both aesthetic experiences and productive aesthetic, creative, productive practices.

Brandon: As you were speaking, I just recalled a news article I came across, I think, just yesterday of a brain surgery in Italy. I don't know if you've come across this? This was a musician. I think he was a saxophone player, and he had to do this fairly serious brain surgery. One of the things he was asked by his medical team was, "What sorts of capacities do you want to preserve? Because we can't guarantee everything." He says, "I'm a musician. I have to continue to be able to play music." So, he played the sax throughout the surgery, throughout the entire surgery. It was really a fascinating, surprising thing.

I think that that's really crucial to think about what insight do we gain from studying the brain. I suppose, one way in which people talk about the relationship of the brain and, say, culture is around this issue of nurture and nature. So, is beauty something that we're naturally inclined to, or is it completely conditioned by our nurture and our culture? Is there anything objective about beauty, or is it completely in the eye of the beholder? Can we gain any traction into some of those thorny questions by studying neuroaesthetics?

Anjan: I think so. There are some assumptions, and even the framing of that question that I'd at least like to examine. One is the notion that is talked about commonly of how things are either culture or they're hardwired in the brain. That is a dichotomy, I think, that's worth at least examining and perhaps resisting.

The example that is clearest in my mind that most people would have a sense of is reading and writing. Most of us, and many of your listeners, will be literate and will know how to read and write. It's a little bit mysterious, why is it that these little squiggles of line somehow conjure up meaning and poetry in our brains? But it's a very specific kind, which is if you know English, then you can read that. If you don't know Hindi, all you see are a bunch of squiggles, right? There's nothing that is penetrating you with respect to the meaning of what those official forms have.

Reading and writing is very much of a cultural artifact. In the long history of humanity, most people have not known how to read and write. So, it's a very much of a cultural artifact that many of us now have the privilege of possessing. It turns out in our occipital cortex, in our visual brain — which carves out the world into different domains — there is a part of our visual system that is very sensitive to people. There is a part that's very sensitive to places. There is a part that's very sensitive to things. It turns out there is also an area that is referred to as the visual word form area. So, there's a little bit of real estate in our occipital brain, in our visual brain, that is dedicated to processing these lines and squiggles into words. On those grounds, you would say this is hardwired. But we've already said this is a cultural artifact. So, the point being that culture still has to work through the brain at a level of the individual. So, culture can have its imprint on the brain, in the same way that we think brains, individual brains as a collective has an influence on culture.

For us, one way, as scientists, that we are always thinking about this is, what's the nature of variability? How do you explain variability? We'll get to beauty in a second. But some aspects of variability are very consistent across people and across cultures. Some vary by culture, by age, by experience, and so on. So, understanding variability is ultimately the core. When things vary by experience, that is still written into the brain. We can still look at the brain to try to understand that kind of variability.

Going to your question about beauty, it looks fairly consistent that it depends on what we're talking about. So, I already mentioned that we carve out the world into people, places, and things. People are generally quite consistent in faces that they think are beautiful. People are pretty consistent in landscapes, natural landscapes, that they think are beautiful. People are very inconsistent in artwork. Architecture seems to be somewhere closer to art than to natural landscapes.

I think the big picture that's emerging out of this is that with the natural kinds — with people and natural environments — we tend to be more consistent. When people say beauty is in the eye of the beholder, my usual response is, beauty is in the brain of the beholder. Our brains are more similar than they're different from each other. So, I think those kinds of natural environments or how our brains evolved tend to be more consistent. But then, human artifacts is where things really diverge. People's response to that are far more susceptible to, again, culture, background experience, education, where you even happen to be living. Even within your town, if you live in center city, or you live in a suburb, or you live — those things, all have a huge impact.

Brandon: One of the things you've talked about in, I guess, defining aesthetic experience or understanding it is seeing it as an emergent property of three interrelated systems, distinct but interacting systems in the brain, right? Could you tell us a little bit about that aesthetic triad, and what we can learn from that?

Anjan: Yeah, so, we talked about it as the "aesthetic triad" that has these three kinds of large-scale systems. One has having to do with the organization of our sensory and motor systems, one having to do with the organization of our emotional systems and how we receive pleasure and reward in the world, and the third having to do with semantics and meaning.

Just to give examples of each of those, a trivial example for the sensory part might be that you can be out at a beautiful sunset over the beach, and you appreciate how beautiful it is. Most people would have some reaction to that kind of a scene. But there's a lot of information out in the world. For example, in the infrared spectrum of the sunset, that we just don't have the sensory receptors to even apprehend that. So, there's stuff out in the world of which there's a sliver that we are even sensitive to based on the design of our sensory systems. So, that puts some guardrails on the kinds of things we can have a beauty experience of. The motor system, similarly, there are certain biomechanical constraints on our motor system. So, when you're watching dance, certain kinds of movements will be regarded as more elegant, more graceful. But movements that don't follow the ways in which our joints work can be almost repulsive at times, that there's something odd about it. That's an example of things on the sensory motor side.

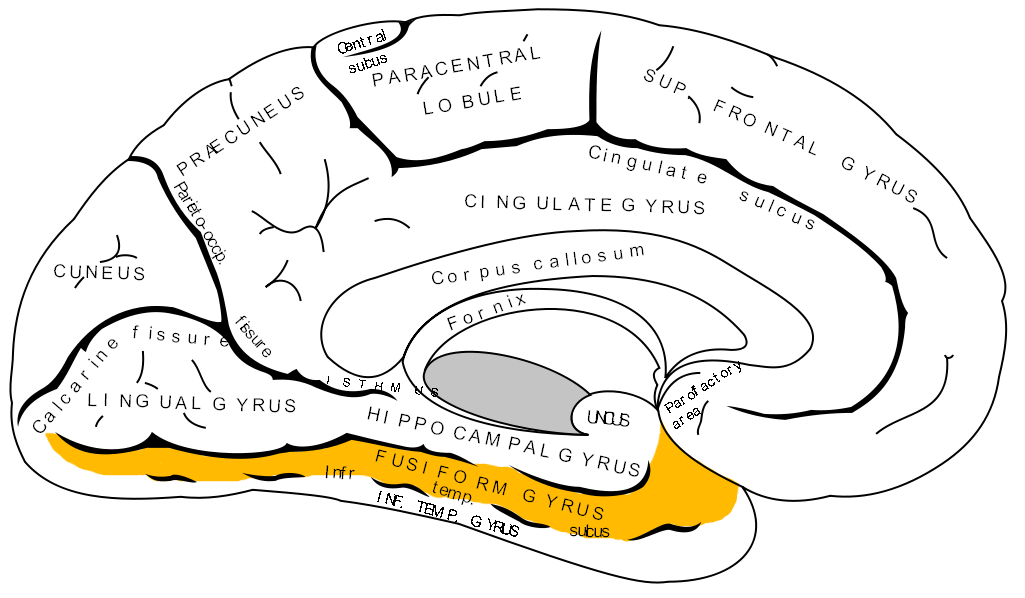

With emotions, especially when we're talking about beauty, pleasure seems to be the most important piece of that. It's that we get pleasure from things that are beautiful. To a first approximation, the experience of beauty seems to be the combined neural activity of the object — let's say we're looking at a beautiful face. The combined neural activity within our visual brain, in an area called the fusiform face area — it's the fusiform gyrus — the activity there and in our pleasure systems, which are in the front of the brain and deep structures, when both those areas are activated simultaneously, that's a biologic description of what the experience of seeing a beautiful face is. The idea is that, these pleasure systems tap into very ancient systems in the brain that apply to food, and sex, and all of the other things that motivate us and drive us in that way.

But when it comes to art and other things, the kind of emotions that are evoked can be quite nuanced. It's not the same as putting a little bit of sugar on your tongue. You can have elements of anxiety. You can have elements of fear. When people talk about the sublime as an important construct of aesthetic experiences, there is a sense in which you're talking about something that is beautiful but also vast and a bit scary. It makes you feel insignificant, maybe, at the same time. So, these aren't simple. These don't necessarily have to be simple emotions. Again, even in popular culture, people pay a lot of money to go watch horror movies. Halloween is coming up, right? It's an aesthetic experience to go get scared, and people are willing to do that. So, the emotion part — this is one area that is active in an active area of research in my world. In the first 10 years, everybody is focused on beauty and pleasure, but now it's more like what are these more nuanced combinations, the combinatorial properties of emotions? How do we even try to get at that?

Then the third part of this which is we were talking a little bit about before around semantics and meaning. But really, how does even the labeling of a work of art having influence and how you think about it, or whether you know something about the particular culture that in which the art was produced? The time, the familiarity of the artwork, for example. The other example I like using is that if you ask most Americans right now, what class of paintings do they like? The most common answer you'd typically get are Impressionist paintings. People love Impressionist paintings. But 150 years ago, when they first came on the scene, they were derided. The salons in Paris didn't even think this was really art. Like, why are we showing this? Our brains haven't really changed in 150 years. So, there's something about the psych guys of the culture over that period went from being really avant-garde, challenging the status quo. The same thing now is the most beloved kind of images that — I mean, college students have those painting, the pleasures of those, in probably every dorm in America.

Brandon: Right. Is there a kind of weighting process? I suppose, what is the relationship between these three systems? I suppose, are there ways in which — to put it crudely, can you add them all up and say, when an experience hits all three systems, it's more beautiful than one that hits only one of them? Is there a qualitative distinction between these? Aesthetic experience, like moral judgments, seem to be a second order phenomenon where we can ask ourselves, yeah, I find that pleasing. But should I? We can have that sort of reflection. I wonder, how does that affect the nature of these aesthetic experiences? Does that moral meaning making dimension have a more privileged space? Are they just all somehow equally weighted in our experiences, if that makes sense?

Anjan: I'd say, when you're talking about the triad, that's one thing. If we add on to that moral valuation, that's another layer on top of all of that, which is something we're quite interested in. Going back to the first one, I was just talking to a museum curator. She wants to do an exhibit in which principles of neuroaesthetics are highlighted as part of an art exhibit. These are very early days in our conversation. But one is to say, let's take this triad and really pick artwork that very much emphasize one of the three, even recognizing that almost always they're intermixed. So, you could imagine very vivid, colorful paintings. The focus did as part of the sensory part. It's like in your face, the sensory qualities of the images. You could imagine the German expressionists or certain kinds of Baroque paintings where the emotions are just jacked up, almost to the point of seeming overly dramatic. But it just hits you in the face, the kind of emotions being expressed.

Then for the meaning part, it's a lot of contemporary conceptual art. The Philadelphia Museum has one of Duchamp's urinals on a pedestal. Look, a urinal on its side has a pleasing shape. I grant you that. But the power of that art is really around the conceptual point that Duchamp was making. I think, with each of these, you can show how the artwork is really pushing more on one or the other of these triads. We were talking about the Impressionists. I can't remember. I'm trying to think of who the quote was from. It might have been Picasso, but I'm not sure. Talking about Monet, saying, "it was just an eye. But what an eye!" So, by that, I think it was really mentioned — talking about how sensitive to the sensory qualities of the image Monet was. I think that's one way in which you can think about how different artworks vary, and how much they weigh on the triad.

The question of morality, I think, is fascinating because it's a whole other system of valuation. What we're talking about is how when we look out in the world, we can classify things by what they are. I know that there's a table in front of me. I know I have a little cup over here, that I just had some espresso so I could be alert for this conversation. But values are a whole other thing, right? It's something we're adding on to that. Aesthetic and moral values are two principal kinds of values. There might be utilitarian values, might be another one that seems to be quite important. Our view is that our brains are very good at discriminating between objects, but sloppy at assigning values. By that, I mean, if you again go back to the ancient Greeks who thought that three fundamental values that contributed to our sense of humanity were goodness, beauty and truth, we think with varying degrees of evidence to back up this intuition is that those get conflated all the time.

In our research, we're finding, particularly with faces, that beautiful faces, if they have various kinds of facial anomalies — these could be scars, these could be birthmarks, these could be developmental abnormalities — that people with typical faces, without even realizing it, make characterologic judgments of those faces as being less intelligent, less competent, less trustworthy, less hardworking, and so on. It's the other side of what social psychologists have talked about as beauty as a good stereotype. Here, you have something that is a person who is beautiful, or has something that's getting in the way of their beauty. People, without realizing it, are then ascribing morality to that, that somehow, they're either better than or worse than. Strictly, based on appearance, that's somewhere along a beauty axis.

Brandon: Is it because we are trying to make beauty a heuristic? Is it essentially operating as a shortcut for helping us navigate through the world here?

Anjan: Yeah, I think it might be. One of the things that we were interested in is — I mentioned this in The Aesthetic Brain, the book you mentioned in the beginning — there's an evolutionary story that is sometimes told and a story that we have told as well, which is there is a built into us is our mechanisms a heuristic, to be sensitive to people's immune status. It's an adaptation to understand how people's pathogen sensitivity. So, if you are particularly easily affected by pathogens, and most pathogens tend to produce disfigurements, whether that's in plants, or animals, or people. It's a signal to say, "Okay. Maybe this person isn't the best possible mate." Not to say that this is all done explicitly. It's all these heuristics that are built into it.

We've recently finished a study that at least challenges that notion, where we went with some colleagues here at Penn who do fieldwork in Tanzania. We did a study with the hunter-gatherer tribe called the Hadza. They are about 500 to 1,000 people of this indigenous culture there that still move around in camps of 20 or so people. So, the question was, would they have the same kind of biases we are seeing very consistently in our studies here? If this pathogen sensitivity argument is correct, we should see it there. Because those are the kinds of conditions in which people think that, evolutionarily, this got built into our brain. But what we find is that they actually don't have the same kind of biases. In fact, if you examine them with these scales that start to indicate how much exposure to non-Hadza culture they have. So, it's a questionnaire that asks things like, "Does a name Nelson Mandela mean anything to you? Do you know any words of Swahili?" So, you get a sense of how much exposure they've had. We start to see, as they have more exposure, these same kinds of stereotypes that we have start to emerge. It's the first paper that I know of — there may be others — that argues that culture may have a big role to play in this.

Once you point that—again, your listeners will be very familiar with the fact that if you think about Hollywood, you think about Bond movies, Marvel movies, Star Wars — I just finished watching the most recent installment of The Lord of the Rings series on Amazon. In The Lord of the Rings, the elves are tall and beautiful and immortal and good. The orcs are distorted and dark and have scars all over their face. It is such a common trope to say someone who's got facial anomalies, disfigurements is bad, is evil. Even if you think about movies we make for our children, The Lion King, one of the most popular movies. The villain is named Scar! It's the only character in the movie that doesn't get a name. So, this is what we're feeding our three-, four-year-olds.

Again, this is an example, going back to a much earlier question you had of ways in which culture and biology interact. In this case, we think maybe the culture is playing a big role in how we've developed these heuristics. We're taught these heuristics.

Brandon: Well, let me switch gears a bit. I want to come back to heuristics in a second, about the heuristics used in science. I want to ask about non-sensory things that we find beautiful. I can understand why, say, from an evolutionary perspective, we would find symmetrical faces beautiful or bodies that signal reproductive potential or something like that. But why is it that many of us find mathematics beautiful? What's going on there? How does that affect our brains?

Anjan: I don't know what's going on in the brain. It is the kind of thing that I think really weighs heavily on the semantics. Meaning, part of the triad. Because as you say, at least, there isn't a transparent way in which our sensory systems are involved.

We did a quick study on mathematics and beauty some time ago. I think it was actually only published sometime in the last year, where we also looked at lay people and people with training in mathematics. They were shown a series of equations, and they were asked to judge the beauty of these equations. The main findings were that people with some knowledge of mathematics were more consistent amongst themselves as a group than people who had no training in math. They were all over the place. One thing that was also true — as the more familiar people were with the equations, the more likely they were to find it attractive. So, in that sense, the first point makes sense, which is mathematicians are familiar with more of the equations. So, they're more consistent that way.

But the one interesting finding was that these formulae varied in how long they were. The mathematicians were more likely to find equations that didn't have a lot of elements in them more beautiful than people who are non-mathematicians. Our guess is that these notions of — elegance is a word that comes up all the time in mathematics. Elegance, there's a kind of simplicity that hides a deeper complexity. That is, I think, what the mathematicians are sensitive to as a form of beauty.

In visual art, for example, people will also talk about unity and diversity, that there is something. You have a lot of diversity, and it coheres around some central theme. In mathematics, I think you're seeing that at the level of quantifiers, and how you can elegantly describe a complexed relationship by something that on the face of it seems much simpler. I think that's what mathematicians are sensitive to. That resembles something that people are sensitive to even within the sensory domain. Is there something coherent across quite a diverse array of sensory stimuli?

Brandon: Yeah, there is. It seems to be like a judgment of parsimony that is behind our assessment of what is elegance, and what's an elegant equation. It has to have a minimal number of terms, explaining the maximum number of phenomena or something like that.

There are arguments here around whether these sorts of — which again is here then, this has come to become another form of heuristic, fields like theoretical physics where many people have come to believe that a mathematical equation or a theory that has beautiful mathematical equations is much more likely to be true than a theory that doesn't.

When you have an ugly looking theory, the assumption is, well, that's likely not going to work out. The history, at least, in the first half of 20th century, it's been quite interesting that a lot of these scientists who stuck to their beautiful equations, even in the absence of empirical confirmation, turned out to be right. Then now we're in this odd situation where some are saying, "Well, for the last 60 years, that beautiful mathematics has not produced any new physics. So, let's stop. All right. Enough with this, with the pursuit of beauty. It's derailing us. It's leading us to invest in money, into things that just aren't worthwhile."

It raises this peculiar question as to whether we should try to overcome our judgments of beauty. What are the conditions under which we should try to somehow retrain our intuitions of beauty? I suppose, if we start to arrest people with scars, then that's a problem in our society. We should stop doing that. But I'm curious as to what you think about at what point do aesthetic judgments become a source of bias, that is something worth reprogramming? What does it take to do that?

Anjan: That's a great question. Beauty is seductive. That's inherent in what we're talking about. Especially when we're talking about people, some of the words that are used, associated with beauty are things like charming and glamorous and enchanting. Those words all come from magic. Beauty casts a spell on us. So, that's something to know about. I think you can be willingly seduced, but you recognize that you are being seduced. Where this, I think, becomes relevant is, again, if we go to this beauty and morality argument. I think it's a mistake to equate beautiful people with people of high moral value and the reverse of that. I think most of us, when we talk about this, agree that that doesn't make sense.

Going back to the Greeks around beauty, goodness, and truth, that's a conflation of beauty and goodness. My own intuition is that there might be a similar psychological conflation of beauty and truth, which may not be warranted. So, I am not a physicist or a mathematician. But biological systems are messy. At least, in biological systems, it's not always obvious that parsimony and the simplest system is the best. Biological systems often end up being designed with a bunch of redundancy in them. So, it doesn't make sense to me necessarily, across the board, that that would be true. I don't see a priori why it would be the case, that theory of astronomy or theory of physics that is the most parsimonious and is the one that is most likely to be true. Maybe that is. That ultimately will be true. On a priori grounds, it's not obvious to me why that is any different than thinking someone who is beautiful is also good, that a theory that is beautiful is also true.

Brandon: Right. That's really the live debate, I think, among many theoretical physicists. There's something else I wanted to ask you about. I've found in my research on scientists that many of them find beauty certainly in the sensory aspects of cells and stars and so on, but also an understanding when you grasp the hidden order behind patterns or the inner logic of a system. It's something like what Alison Gopnik describes as "explanation as orgasm." What is it about conceptual work? It's pleasurable to us. It's not a sensory experience. So, how is it that we find a beauty in that or associate beauty with that?

Anjan: Some people have argued that we are infovores, I think. It's that word that comes up. That we really desire, we consume information. We consume new and better information. Built into our evolutionary brain is the idea that pleasure drives a lot of what we do. If we get pleasure from new information, that this is of adaptive significance. You might be more likely to forage and figure out signs that point to better nourishment in the environment. That's the kind of information that delivers something that is useful for your survival. That's a broad notion. But the general idea of being, once you recognize a gap in your knowledge, that closing that gap itself is a source of pleasure and drives us to want to do that.

One notion that is becoming more salient in my world are these motivational states, like curiosity. What's going on with curiosity? Why are some people more curious than others? The people who are more curious tend to be the people who also get more pleasure from having that information gap closed. So, I think it is this way in which discovery is pleasurable. As Gopnik mentioned, you see in infants, when they figure something out, there's expression of joy on their face. There's no mistaking the expression that they're demonstrating. I think that still remains in people. Especially, I think, scientists, if they're true to their roots, I think what drives a lot of scientists is this desire to know, desire to discover things. That's motivated by the kind of pleasure you get out of that.

Brandon: In your own experience, in your own research, are there moments of such pleasure of insight and understanding that you would consider beautiful, that stand out, too?

Anjan: Yeah, I was thinking about that a little bit. One, that is not about my research. It's almost going to be a cliche because probably many, many scientists would give this answer. It's Darwin's theory of evolution. I've heard and read about it for the last 40 plus years. It never ceases to make me wonder and feel awestruck about this simple formula, that if you have variation, selection upon that variation and then replication, that's all you need. Everything follows from that. As we were talking about before, the enormous richness and complexity of the world of life really is predicated on those three pieces in this formula. It's just extraordinary. It just blows my mind every time I think about it. Every time I reread another version of laying that out, it gives me chills sometimes just to think about that.

In my own work, I certainly haven't had any of those kinds of moments. But some moments of wonder, I can think of one very early on when I was a postdoc. I was studying a disorder, a neurologic disorder that is called hemineglect or hemispatial neglect. This is a disorder in which people often have strokes typically to the right side of their brain. They might act as though the whole left side of the world doesn't exist. Phenomenologically, it's the most amazing thing that they act as though even their left hand, they don't think it's their own hand. Sometimes you ask them to draw something, they might drop part of something but not the left side. It's one of the most extraordinary displays of what can happen in the context of brain damage that is so counterintuitive. To my knowledge, there was no a priori account of how our brain is aware of the world and our understanding of consciousness that could explain this as a phenomenon. So, that was one of the first things I was totally fascinated by.

In studying this — I remember this was in Florida, in Gainesville, Florida. I was studying a patient. I had been giving her some various stimuli to interact with. All of a sudden, I started realizing that there was a direct mathematical relationship between how much stimuli I presented to her and what she was aware of, and that this could be described by a power law. It blew me away for a couple of reasons. One is, this very strange, qualitative experience. Some of it could be captured by a very simple mathematical formula.

Now, it turns out that in the 1970s, Stevens had described power laws in psychophysics, but I didn't know that literature at all. I only discovered that later. There, I'm in front of this person and saying, "How is it this qualitatively bizarre phenomena can be accounted for by a simple mathematical formula?" Then that led into a whole line of research. But for me, that was one example where there was a discovery there, and something that we always struggle with if you're studying aesthetics, or you're studying cognitive neurosciences. What's the relationship between qualitative experiences and our ability to quantify it? If you're going to do science, quantification still is the lifeblood of what we do so that we can test theories and make statistical inferences. But we're still trying to get at that qualitative experience. Here was the first time I saw right there, here was a mapping of something qualitative, fuzzy about consciousness that boil down to a simple power law. So, that was a very exciting time for me.

Brandon: Well, let me ask you: Taking the state of neuroaesthetics today as a whole, are there any big open questions or any big puzzles where you would say, "Wow. If someone could answer this, that would be really beautiful?" If there's something like that, that you and your colleagues would—

Anjan: I think there are so many questions that are live right now. One of these, as I mentioned, is the nature of his aesthetic emotions. Is there anything special about aesthetic emotions? Are these just other emotions that get implemented in certain contexts? It's one thing. I think the question of cross culture aesthetics is really big right now. Because we want to say that certain experiences are universal, but unless we actually go out and find out, are they universal, we can't build a theory of universality based on American undergraduates and European undergraduates. This is much of the state of psychology.

The question, is beauty universal? The malleability of our response to beauty, I think, is an important question. The ways in which it matters. This may be less of a scientific agenda and more of how do you change the zeitgeist, that there is a way in which people in the US often relegate studies of aesthetics to — it's a fruitless pursuit. It's not that important, that the American ethos is very much of I can do. Let's fix it. Technology is going to solve our problems. This beauty stuff, that's for the privileged few who've got nothing better to preoccupy themselves with. I've happened to think that's wrong, but it has consequences of funding and vehicles in which to do the science.

One challenge, I think, is to really get people around to the idea that this stuff is not trivial. In a peculiar way, the pandemic perhaps helped a little bit with that, which is that people found themselves confined to their spaces. All of a sudden, what's the environment in which they are — people's children, do they have a space in which they could actually engage with online learning or not? People cared about their garden. All of a sudden, when we were tethered and no longer as easily engaging in — at least for many of us — our manic lifestyles, all of sudden, we're stopped short. One part of that, I think, was the emergence of what is valuable. What is valuable around me? What is valuable in my relationships? What is valuable in the physical environment? What is valuable in the objects in which I interact with.

The other extraordinary thing, which also gives me chills every now and then, is that the pandemic is the one thing that everybody in the world experience simultaneously. The version of it might be different, depending on resources of countries and the response, the medic healthcare system. This is a shared experience of everybody in the world, that I don't think there ever has been something of that scale. So, I'm hoping. My belief is that it has, at least for a slight time, cracked open a window into people saying, "Oh, aesthetics is important. It really mattered." Now, whether that window stays open, I don't know. But I hope so.

Brandon: I hope so, too. Yeah, I really, totally agree with that. Let me ask you for a last question. The modal field, I guess, that we think about when we study aesthetics as art. I wonder, do you see any new insights we might gain if we looked to science as the space in which aesthetic experience happens? How that might open up new avenues, inform us in different ways?

Anjan: A couple of things. One of the areas, I think, which you have been pursuing is what motivates scientists to actually do this. I do think that aesthetics and beauty is part of that, that we're really — this gets both to the beauty of the theories we come up with, how much can you explain in a more simplified version. But also, this desire to close information gaps, which is an aesthetic experience center itself. So, I think those are very much driving forces behind many scientists.

I do think, what we were talking about before, that there is seduction of beauty, that scientists need to also be careful about. So, then science becomes perhaps also a case study of where values help us and where values can lead us astray with respect to beauty. So, I think science would be interesting that way.

Then there are all sorts of subsidiary things, which is data visualization is a big topic right now. I think this capitalizes on the same idea if you have a very beautiful display of data. On the one hand, it might communicate information in a transparent way or a more accessible way. But there's also that other side. The dangerous side of it is that if it's very beautiful, people who read it or reviewers are going to think, "This must be right." Something that's listed in a table as opposed to a beautiful infographic. You look at the table, maybe you'll read it more critically. The same information presented graphically say, "Oh, that's so elegant. It must be right.

I think science then becomes about uses. We spend a lot of time on our figures, by the way. Don't get me wrong. Because we appreciate that a good figure is going to get you more eyes on your work. So, I think we are both seduced by beauty. We use beauty. Sometimes we hope we will fool other people with the beauty of our work.

Brandon: Yeah, or at least persuade people when we think we're right. Anjan, thank you so much. This has been really an insightful conversation. In the show notes, we'll direct people to your books. Are there any other references to which you would like us to direct our listeners and viewers?

Anjan: I have a Psychology Today blog that is — I think it's called Brain, Behavior, and Beauty or Brain, Beauty, and Behavior. I can't remember which order in which it goes. But one of the things we do in that is whenever we have a peer reviewed paper, we try to write a blog for the lay audience to communicate that information. So, it's a way to get at some of the latest research coming out of my lab written for a non-scientist audience to get the word out.

Brandon: Excellent. Great. We'll put up a link to your lab and to the work you're doing there as well. Thank you again. This has really been such a pleasure.

Anjan: Yeah, it's been great. Thank you for having me.

What did you find especially interesting or striking about this interview? Do let me know - I'd love to hear from you. I'd also love any suggestions about future posts and questions/topics to explore.

If you found this post valuable, please share it. Also please consider supporting this project as a paid subscriber to support the costs associated with this work. You'll receive early access to content and exclusive members-only posts.