Finding beauty in ... viruses?!

With the world still recovering from the coronavirus pandemic, the last thing you might expect someone to say about a virus is that it’s beautiful. But I recently interviewed a scientist who calls the virus his first love.

Dr. Mark Painter is a postdoctoral research fellow at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. His research focus is on immune responses following SARS-CoV-2 infection and vaccination, and his work has been published in leading peer-reviewed journals such as Science Immunology, Nature Medicine, Science, and Cell.

For Mark and many biologists like him, beauty isn't simply about visually captivating images under the microscope. Rather, it’s principally about the joy of understanding something new. In our engaging discussion, Mark discusses what drew him to the study of immunology and why the beauty of understanding is so crucial in science.

Our conversation also touches upon the urgent need for open, honest conversations between scientists and the public. The recent pandemic has revealed a concerning gap in public trust in scientists, and now more than ever, it's essential for researchers to engage in genuine dialogue with the communities they serve. Mark describes what such conversations might look like and how they can help cultivate a renewed public trust in science.

Join us on this exploration of the beauty concealed within the world of viruses, and learn how the quest for scientific understanding can shed light on even the darkest corners of our natural world. You can watch or listen to our podcast episode below. An unedited transcript follows.

Subscribe wherever you get your podcasts: iOS | Android | Spotify | RSS | Amazon | Stitcher | Podvine

Interview Transcript

Brandon: Mark, it's such a delight to have you here. Thank you for joining us.

Mark: Yeah, thank you, Brandon. It's great to be here.

Brandon: Well, tell me. What drew you, what attracted you to study biology and then virology in particular?

Mark: Yeah, it's a great question. I think like a lot of scientists, I think it's a common story when I talk to my colleagues, that you can trace the beginnings of the interest in being a scientist, being a biologist, back to early childhood. I remember really loving — I always love plants. I love animals. I love being outside. My dad knew a lot about the forest, about the plants that were out there. I would go out with him foraging, fishing, hunting, and just being out in nature with these things that I really loved. So, I think it really started there. But that beginning point is really a wonder about nature. I wanted to learn about all the animals in the world. So, I would read. I had these books of records from animals, like what's the fastest animal? Which animal goes the deepest in the ocean?

I had all of this interest but there's a difference between, I think, that initial wonder about the natural world and actually wanting to become a scientist. For me, it really, I think, was thanks to having a couple of really great Biology teachers in middle school and in high school that I can remember. I can remember being in middle school biology class, just recognizing that there were so much more to the things that I already love. You love plants, you love animals. But they're made of cells. It's an animal, but it's made of cells. Inside the cell are all of these different components, all of these different organelles that can perform different functions. It was opening my eyes to see that there's — it's not just about knowing that the cheetah is the fastest animal on land. There's an infinite world of things you could know about these things. And so, that was really ripped open for me in middle school and then in high school with a really phenomenal biology teacher, who was able to communicate the depth of what we already know and just how fascinating it is, like how amazing it is that we've been able to learn so much about the world. And so, that really kicked me off to want to study biology in college.

Then I actually had to decide to actually become a scientist. A really interesting conversation with a mentor when I was a student in college. Because I was torn, like, should I study medicine? Should I become a medical doctor? Do I want to be a scientist? My mentor at the time sort of asked me one day. "Mark, when you think about cancer, do you think about that person who has cancer and wanting to care for them, accompany them, treat them as best you can? Or do you think about those cancer cells and the mutations they have, and the reason the immune system hasn't gotten rid of it yet?" I said, "Honestly, I think I'm more about the second one," which made me feel a little bit like a bad person. But it also revealed that, for me, maybe not everyone is called to be a scientist. But for me, I have this particular fascination and interest in those questions. That really was a clarifying question for me, that sort of freed me to be honest about what I find fascinating and beautiful in the world, and to pursue it full on, and not be scandalized that I'm not doing something else that might seem like the better thing to do on the surface. So, that's how I decided to become a scientist.

Then you asked about viruses in particular. I decided to do a PhD in immunology, because I think the immune system is the coolest thing in the whole world. I could talk about it forever. But if you'd asked me — the immune system is broad. There's a lot of aspects of an immune response. There's a lot of things that the immune system is fighting. You have autoimmunity, viruses. You have bacteria. You have cancer. If you'd ask me what do you want to study, I would have said anything but viruses. Viruses are boring. They're so boring. They're just like little pieces of genetic information. I'm not interested in viruses. But when you start a PhD, you have to rotate in a few labs. The first lab I rotated in, I actually was so naive. I didn't set up any of my rotations in advance. And so, all the labs I wanted to rotate in were full.

But there was this lab, which was a great lab, that happened to have an opening that studied HIV. So, I took it out of desperation, needing a rotation and then really fell in love. I really became fascinated by this little virus, HIV — the virus that causes AIDS that can do so many things with just nine genes. HIV only has nine genes. I became totally fascinated by the intricacies and the ways that such a simple organism like the HIV virus can interact with and hijack our normal cellular processes, our body, to avoid the immune system, to cause an infection that lasts your whole life. I became totally, totally fascinated by it, to the point that now even though I've gone back to studying more immunology after doing really a virology PhD, immunology in name only. Now I'm back to doing more immunology research. But still, very much focused on viruses because of that kind of surprising discovery of a fascination I didn't know was there.

Brandon: Was it a fascination with the structure? Was it something about elegance? How would you characterize what was it that led you to — it sounds sort of odd falling in love with the HIV virus. It's like falling in love with a terrorist or something. Say a little bit more about that. Was that an experience in particular? Say a little bit more about it. How would you describe that key characteristic that drew you to that?

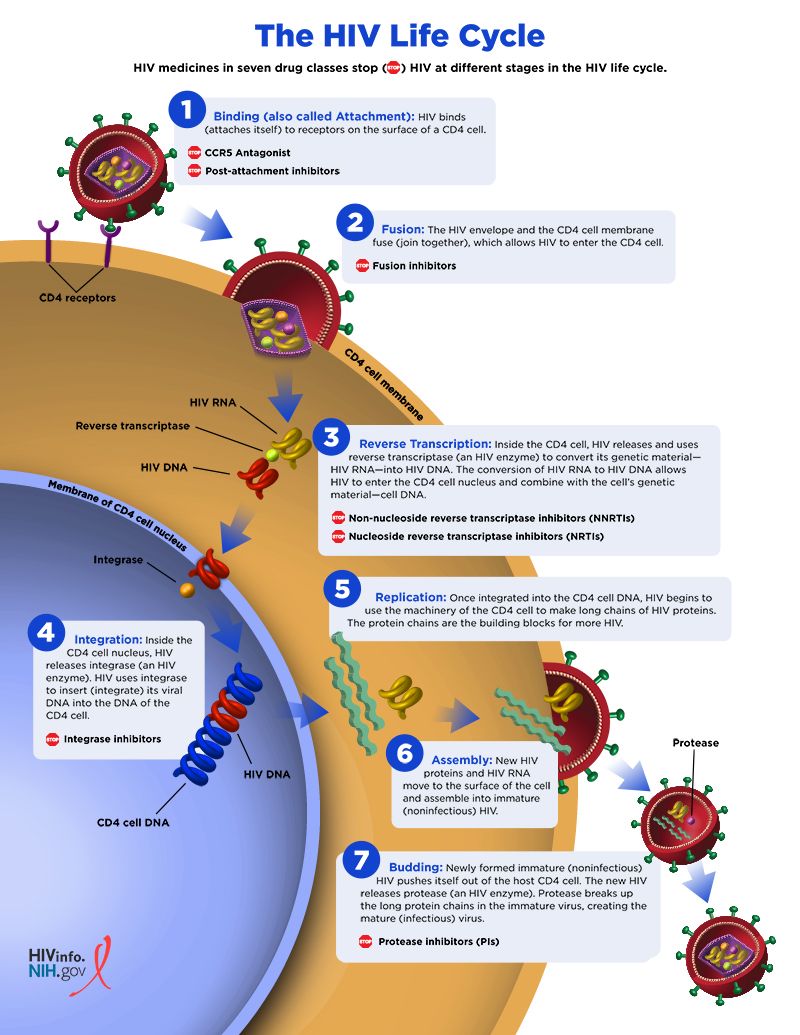

Mark: Yeah, I think it's funny that you said that. Because when I present on it, I often will put up a little picture of the lifecycle of the HIV virus and say, "This was my first love." Not really. But in terms of as a virologist, as an immunologist, I really did fall in love in a certain way — in the same ways that you fall in love with a person. Maybe there's an initial attraction. Then you start to notice all of these little things about it that draw you in deeper, that make you more interested and more fascinated in this particular thing, this particular person — in this case, a virus. I think you use the word elegance, which is a perfect word. Because I think the initial attraction was to that. Like, how can so simple of an organism be so diabolical in the ways, with such simple parts, the intricacy, the precision with which the virus is able to overcome all of our defenses?

We have so many layers of defenses to protect us against exactly this kind of virus. We've been getting infected by viruses of the same type as HIV for 450 million years. Vertebrate animals have been getting infected by retroviruses like HIV. We have evolved over those 450 million years. Countless defenses against these viruses, to the point that in a world full of retroviruses, almost none of them can infect us and can infect humans. Because we have such good defense against them. And yet HIV, with just these nine genes, is able to find a way around everything that we have in place to do it, to establish this infection, which is marvelous in a terrifying way because of its impacts on human health. It's caused an absolutely horrific pandemic. It caused so many lives, so much suffering. And yet, the virus has no mal intent. It's an evolved organism that is simply persisting and poses a really fascinating challenge to a scientist to understand exactly how it's achieving what it's managing to achieve, and also how we can try to counteract that.

Because as much as you might be in love with the virus, what you're really in love with is this fascinating problem, this fantastic set of processes that are happening that pose a challenge, to try to understand them better so that we can actually help people eventually. It would be the goal.

Brandon: Well, what exactly are viruses? Are they organisms? Are they alive? Are they machines? How do you understand what these things are?

Mark: That's a great question. I don't think there's consensus. I think of viruses as an essential — it's almost hard to imagine life without them. But sort of an almost inevitable byproduct of the process of life as we know it. In every way, whether the virus itself is alive, the virus is very much involved in the process of life.

Basically, what a virus really is, is just a piece, a small piece of genetic information that has the capacity to replicate itself. You could think of us in a reductive way as a big set of genetic information that is able to reproduce ourselves. And so, all of life falls into this paradigm. It's really the beauty of evolution, to get at the word beauty here. But the marvel of it is that it's a very, very simple paradigm that generates unimaginable diversity of life and so many beautiful things, which is this simple paradigm that any genetic information that can replicate and persist will. The genetic information that persists is here today. Whatever didn't is gone, has gone extinct, or never really established in the first place.

And so, through that simple paradigm, you have this process through random mutation that diversifies into so many different life forms that are able to persist, that are able to go on reproducing and continuing to propagate that genetic information through history and all of the diverse forms of life. A virus is really just the simplest version, which is a tiny piece of either DNA or RNA that can go into a cell and hijacking the normal machinery of a cell, make copies of itself, exit the cell, and go on to infect another cell and another organism. They will do this forever until they die out, just like everything else that's alive.

People don't think of viruses as alive, because they don't acquire their own nutrients. They can't propagate on their own. But scientists will use the word like an obligate intracellular parasite — that once it's a parasite that goes into your cell, and once it's in there, the cell is obligated to provide for it. Because the virus, that's what it does. It basically hijacks the normal systems in your cell and turns that cell into a virus factory instead of whatever that cell was supposed to do before.

Brandon: Right. Incredible. Tell me. We started talking about beauty, and you've touched on this to some extent. But where in your work now would you say you encounter beauty? What is that? Does that word actually mean something in relation to your experience of work? Where would you encounter it?

Mark: Yeah, I would say yes. It has to do a lot with my work. You encounter it everywhere. I think people would be amazed if you spent time around scientists with how often the word beauty is used. It feels like several times a day. In conversations with my colleagues or even just sitting by myself at my desk, I will say it's so beautiful. It's so beautiful. It's one of the most common words in science to describe a study, an experiment of finding. It's beauty. I think it's interesting to reflect a little bit about why. Why do scientists gravitate toward this word of all the words? What do we really mean when we say beauty? So, I think a lot of people, there's kind of the — I don't know if we curse on this podcast.

Brandon: That's fine if you like to.

Mark: I remember in high school, with Facebook, there was this I f****** love science. Everybody followed it. It would just show explosions or pictures of a microscope or something. Those things are cool. They make an impression on you. But it's not really science. It's more nature, that the universe exists is cool. And we love that. But science is this process of discovery.

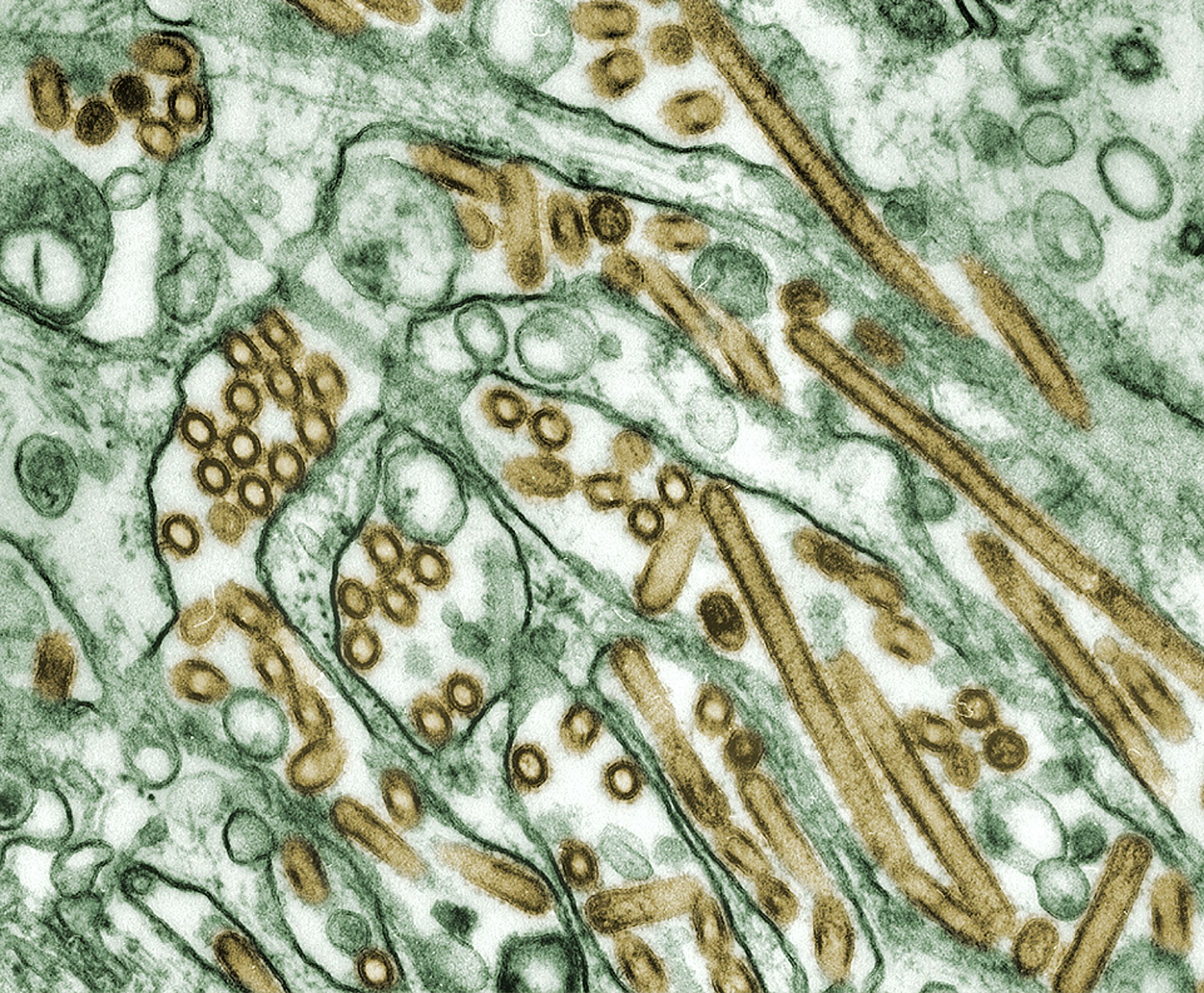

I make that point to contrast what I would say is something being pretty and something being beautiful, which is that, in science, you can generate a lot of pretty images. If you look under a microscope at a virus, you can choose what colors you want to use. We have all kinds the technology. It's amazing now to zoom in, to look at life in ever greater detail, to label intricate pieces of the cell with fluorescent signals that make them light up in these brilliant colors. You can generate these very aesthetically beautiful images that leave an impression on you, that are very pretty. But if they don't communicate something, they don't reveal something about the world, they actually aren't that beautiful to a scientist. Just a microscopy image of the inside of a cell can look very pretty. But I wouldn't say, "Wow, it's so beautiful." Because when I use that word in science, what I mean is that I understand something now that I didn't understand before. I think this is what I find really interesting. I think just observing how I and my colleagues use the word beauty without even thinking about it, what we mean is, now I understand something I didn't before. It's beautiful because it revealed to me what I wanted to know.

I have countless examples. I was presenting a classic paper in immunology last week. They have what is objectively the ugliest image you've ever seen. It's like a fuzzy, gray box with this ugly, contorted strand running through the middle. It's not a pretty picture. But it was the experiment that definitively showed one of the fundamental things that shaped our understanding of how immune memory works, and how we're able to generate immune memory against every virus that exists. And so, to me, it's one of the most beautiful things I've ever seen because you see it. If you just see it for its aesthetic value, it's very low. But if you understand what it's showing you, it's so beautiful because now you see reality in a new way. And you see exactly what you wanted to know. So, I think that that is where we encountered beauty or where I encountered beauty as a scientist.

We had a visiting lecturer from the Rockefeller University, Gabriel Victora, who's one of my favorite scientists. He doesn't actually work that closely on what I studied. But from afar, I really love what he does. Because he comes up with these really elegant techniques. There's a component of elegance to reveal very simple but fundamental things about the immune system. Not needing to know about the jargon too much, there's this question when you're responding to a virus for the second time. Are the cells that go into the lymph node into this special thing called the germinal center reaction, are those the same cells that responded the first time you saw the virus, or are they new cells? It's a simple question, but he's developed this really elegant technique that reveals it through these absolutely stunning microscopic images of what's happening inside of a mouse, where you can see the difference between a new cell and a cell that was activated during the first exposure.

He was presenting last week. When he puts the images up, they're just so beautiful. I'm so moved, almost to the point of tears. Not because there's a lot of pretty colors. There's a lot of images in science that have a lot of pretty colors, right? His images do have a lot of pretty colors. But what makes it beautiful is what it shows so clearly because of the elegance of the system. So, I think beauty really is this experience of understanding something. It's a phrase we use either when in the moment of understanding like it's so beautiful, but also when we see that something has the potential.

So, I was presenting last week. My boss — I put up my experimental design — he said that's a really beautiful approach. We haven't even done the experiment yet, but the approach is beautiful because you can see that this will reveal something about reality to us. And so, as a scientist, because that's what we are so fascinated by, a thing that's beautiful is the thing that fills that desire that we have, then meets it in an adequate way. That actually reveals it, if that makes sense.

Brandon: Yeah, absolutely. This is one of the key findings in our research on scientists. There's certainly, as you say, the beauty of pretty pictures and the sensory beauty that could be sometimes stunning if you're an astrophysicist or something. There's also maybe beauty as a heuristic, as as a guide to truth, and so forth. But really, what seems to be fairly universal among scientists is the beauty of understanding, this ability to glimpse the inner logic of a system or grasp the hidden order that's underlying some data.

Would you say that this sort of beauty is about — does it have to do with getting at better explanation of why things are the way they are? Or is it just simply even grasping this is how things are, even if we don't quite understand why? Is it just the revealing of something hidden, or does it also have to do with explaining causality or something to that level?

Mark: Yeah, that's a really interesting question. I'll probably cop out and say that it's a little bit of both. There's a certain marvel just in discovering the new, something new. Something that was obscured before becomes clear. There's a beauty in that moment. But, of course, it's more beautiful if it's something that also unlocks a bigger picture. That shows even more.

The student who works with me now did a simple experiment last week. As we were looking through his data, at a certain point, I said, "Wow, this was a really beautiful experiment." Why? Because in a little piece of his data, that revealed something clearly in a way that none of our previous experiments had done it. It changed how I understood, not the entirety of our project but a certain section of our project. It made everything fall into place. The things that I thought I understood before, now that I see this piece, all of that makes more sense. And in that moment, you really sense that something beautiful is happening, because you could taste it before. You were already studying those things before. But this new piece, everything suddenly makes so much more sense in light of this new piece of information. I think that those are the most beautiful moments. It's not only when you discover something new, but when that new thing that you discovered also makes everything else more beautiful too. Because now everything else makes even more sense than it did before.

I think it's analogous. I don't think that this is unique to science. If I think of my relationship with my girlfriend, if she suddenly were having coffee, and she tells a story about her childhood that shaped her personality, there may be five quirks of her personality that I already love, that I already noticed and love. But this story reveals the origin or some part of the origin. There's still more to be discovered about the origin of those quirks. But now the origin is revealed. My tenderness toward all of those things that I already noticed and love is more because I know more where they came from.

Really, my experience of doing science is very much — it's a form of intimacy. You're always. You never exhaust your relationship with a person, with another human being. There's always more that you could know. You could always become more intimately familiar with that person. I think it's really the same with science, that there's always more we can know about reality. We do experiments to grow in intimacy with reality, with this thing that we love, whether it's a virus or a person.

Brandon: All right. Great. Can beauty actually help us better understand things? So, we're talking about the beauty of understanding. But can beauty be useful in some way to help us understand? I'm thinking in terms of particularly science communication. Do you find that you have to think about beauty in some way in order to help people better understand?

Mark: Yeah, I think I do. Yeah, I have a lot of opinions about this as a vaccine scientist. In 2022, there's a lot of conversation about how the public perceives what we discover in science and how it's communicated to everybody. I do think maybe — I don't know if talking about beauty per se would help. But talking about these things, like, why do we do science? We do science because we want to understand the world. In science, then what you discover isn't a prescription. It doesn't tell you exactly how you should behave. It doesn't tell you exactly what you should do, but it tells you more about how the world is. It's never the final story, but it's the best we have. And it's beautiful. It's not just the best we have, so we have to suck it up and deal with it. It's the best we have. It's really amazing that we can know what we do know even though we never know everything.

I think that, too often, science gets wrapped up in messaging. That there's a certain, "Because this is true, it would be great if people behaved in this way for this desired outcome." But then, instead of communicating the totality of that, you just say, "Science says you have to behave this way." You have now stripped away all of what's interesting about science, all of what's beautiful because you lose all of the nuance of why you would want to change your behavior in response to science. Because when I see something, a new discovery, it makes me want to change how I do my research. Because I know reality is different than how I thought it was before. So, if I know that a virus is airborne, I want to wear a mask because I want to protect myself and the people around me. But if I'm just told, "Science says you have to do this," I lose the fact that this is really me responding to what science is telling us about reality.

I think that we probably could benefit from trusting people more, giving people more benefit of the doubt that you can understand these things. If we explain this is what we think we know, this is how we think we know it. We don't know everything. But based on this, we would recommend this for these reasons. Let people evaluate, that the reasons are reasonable and not just you're being told you have to do this.

Brandon: Yeah, that's great. I want to ask you a bit about the consequences of encountering beauty. One of the things we find in our research is that frequently encountering beauty in scientific work is associated with higher levels of well-being. So, everything from mental health to sense of meaning and purpose and overall life satisfaction and so on. Do you find that encountering beauty in your scientific work has an impact on you personally and your life as a whole?

Mark: Yeah, I think, first of all, a scientist is a human being. So, I don't suddenly become not my full human self when I go into the lab and start doing science or sport or start reading the most recent publications in my field. I'm still a human being, a human being who encounters beauty, who is in wonder in front of the world. It's going to be happier. It makes perfect sense to me that a person in whatever they're doing that thinks the world is beautiful. Because of something that happened, maybe they fell in love. Maybe they saw the sunset. Maybe they saw a really cool experiment. Something has made you think that life and the world is beautiful. You're happy, right?

I think yeah, of course, as a scientist, experiencing beauty at my work is part of experiencing beauty in my life. It makes me more convinced that life is a good thing, that I'm happy to be here, that the world is a good place for human beings to be. I don't mean that as a cop out. I do think I chose to become a scientist, like I said before, because I have a particular interest in these things. I chose to become a scientist and not a medical doctor because of a particular fascination. And so, to find beauty in the thing that you give so much of your life to — that is such a part of your vocation as a human being, your work — it contributes in a different way, I think, to your level of satisfaction. That if I only see beauty on Saturday morning walking through the park, then nine to five — or as a scientist, much worse than nine to five — Monday through Friday, you'd be miserable. Because you think beauty only exists out there.

Seeing beauty in work, for me, is what keeps me going and is what makes it possible to be happy working long hours, to be happy continuing to do research in a world where so many people have no interest in what scientists discover anymore, discount whatever scientists find as part of whatever the elites are saying, to stay motivated, to keep working now. The fact that it's beautiful is really important to me.

Brandon: Well, what are the obstacles to encountering beauty in science?

Mark: Yeah, I think there's a few. I think, honestly, the biggest one is not to be too political. But it's the reality. Everything I've said is about you have this fascination. You have this wonder. You want to do it. You pursue a career in science. It's beautiful. But it's a career, right? We live in a capitalist society, which provides many benefits to us and is efficient in a lot of ways. But science is wrapped up in that. And so, to be a scientist is your career. It means it's your livelihood. It's how you feed yourself. It's how you pay your rent. That brings a lot of stress into a process that isn't just about beauty anymore. It's also my livelihood.

It's expensive to do science. The experiments are very expensive, which means you have to get funding. There's never enough funding for all of the people who have a passion for science. So, now you're competing for funding. If you don't get it, you lose your job. You lose your benefits. That adds a level of stress. I see it for many people, for many scientists who had the same desire that I had. They went into science for the same reasons as me, can totally lose sight of the fact that it's beautiful to go into work every day because of the stress, because of the pressure.

It also is really bad because science done properly, your interest is only to understand reality, however it is. So, if I'm studying drugs for HIV, like I did in graduate school, if the reality is that my drug doesn't cure HIV, all I want is that my experiment shows that. As if scientists doing science truly, the most beautiful experiment is the one that reveals that the drug doesn't work. But as a person whose career requires that my experiments are successful, that the drug is successful, you can start to think reality is only good if the drug works. And so, then now you become contorted. You can start getting into the pressures, to manipulate data, to try to set up experiments exactly right. So, you're no longer interested in reality as it is. You're interested in a certain outcome, which I think is really dangerous for science. It's wrapped up in the fact that the people doing experiments are doing them with the purest intentions, but it is their career. And if they don't get the right outcome, they may not have funding to do more experiments.

So, I think that that is really the biggest obstacle. I think it's that the funding structure is short-term commitments for grants that reward results rather than the scientific process. So, you may do all of your experiments perfectly well. If your results aren't interesting or aren't helpful, they don't fix society, you may not be competitive for your next grant. I think that that really is the biggest obstacle. It's the fact that you have this beautiful pursuit, but it has to manifest in society. I don't think there's an easy solution to that. It's part of the reality of being a scientist in society today. It's finding a way to stay attached to the beauty of science despite all of these things happening around you. But I do see that as the major obstacle.

Brandon: Okay. So, you were talking about some of the challenges to encountering beauty in science. This comes up a lot when we talk to scientists. Many of them talk about the pressure to publish or perish and to keep getting grants, and even the obstacles to intellectual humility, having to really oversell the kinds of claims you're making and not really be able to be honest in pursuing the kinds of questions you're interested in or even reporting null findings and so on. So, what helps you in the face of those obstacles? What allows you to remain grounded, I suppose, and not be sidetracked?

Mark: Frankly, it's hard. I, actually, among my co-workers, happened to be one of the happier people, I think. Partially because I do believe that if you do science well, if you stay attached to the beauty of what you're doing, there's plenty of motivation there. I will keep working hard in trying to be successful because I'm interested in the stuff we do because it's really cool. Because they pay me to do it. I do sometimes have to pinch myself that they're paying me to go in and spend this research money that come from free donations or from taxpayer money. So, there's a certain obligation to it but to use this to do what I think is the coolest, most interesting stuff in the whole world.

So, they may not pay you that well. They don't. The benefits may not be that good. They're not. But I can provide for myself getting to do exactly what I would want to do, like what I couldn't have imagined getting to do. And so, the fact that it's so beautiful is enough motivation to keep working hard. You just have to trust that it'll work out, that the people who do it the right way — who stay attached to reality, who publish things that are real, who advertise only the true results — that eventually it works out in the end. For me, I can go on only if I have that hope, at least. Maybe it's not a certainty. Maybe it's a little bit naive, even. But it lets me keep going and keep working. And continue to see that doing science is beautiful. It really is. There's a value to this. It's good that it's being funded. It's good that we're here doing this work. It's worth doing it even in this fraught climate of the research world.

I don't know if that's the most satisfying answer. I know a lot of my co-workers don't find that to be the most satisfying answer. But I think that's what we have. As scientists, in many ways, you're not part of the normal economy. Society could stop paying astrophysicists and go on just fine. Society could stop funding my research and go on just fine. We may not respond quite as well to certain diseases. We may not develop vaccines, but they're vaccines we didn't have 20 years ago, and we were okay. And so, in a way, we live off of the free interest of the world in what we do. I don't feel a sense of obligate, like that the world is obligated to keep doing it. I feel more grateful that the opportunities exist at all.

I think that it is — I would love for there to be more funding. I would advocate for more science funding. Absolutely. And stabler careers and longer-term commitments for grants, I think, would really help people. There are some systems that do that, and you see the benefits of it. If someone has 10 years of funding and a stable career, they can be much more free as a scientist to be creative and explore the research freely, and with a joy. So, I think there are solutions we could have. But I think almost fundamentally, doing science is this kind of gratuitous thing that we do because we're human beings, and we want to know the world. And so, I think it'll probably always be something that science has to deal with as we try to fit into a world where you also have to get paid and have a job and things like that.

Brandon: Right. Yeah, that's certainly, I think, an important thing to keep in mind. I guess it's the sense of gratitude that you mentioned. The other issue I wanted to ask you about, particularly since you're working on vaccines, is the current pandemic we've been going through and the skepticism that a lot of people have expressed in science and in scientists and in vaccines. Could anything have been done differently over the last couple of years to have made that process better to perhaps have improved the public's trust in science? Could beauty have been useful in that process, do you think?

Mark: Yeah, I think that's a great question. I think anyone you'd ask, even if you ask Tony Fauci, he'll tell you, yes, there were things we could have done better. Absolutely. I think certainly you can see that, at some point, we went a ride. Things didn't go the best way they could have gone. I don't think you can blame anybody because the pandemic was such an event in history. You had to respond so rapidly, that inevitably some mistakes are going to be made. So, I would be careful not to cast blame.

But reflecting on it, I would say, you see what seems to be a growing mistrust in science. Almost in reflexive response to that, I would say, less talked about a growing over trust in science too. That as a scientist, there should be a healthy recognition that any experiment you do, you never have the whole truth in your hands. You never actually have the truth. You have some understanding of how the world works in that specific scenario that you executed your experiment to study, and you hope that that's broadly applicable, and that the insights you gained from it will hold up and will remain true.

You have the analogy of people looking at an elephant, but they can only see one part. If you only see the foot or the tusk, or the the ears, the tail, you would understand something about an elephant but you wouldn't have the whole picture, right? Science is always playing in that field. Whenever you think you see the whole elephant, you don't. You never do. You're only ever seeing a part. And so, I think keeping that in mind is really important as a scientist and natural to a scientist and less natural to the public, where we learn science in school as just, "This is the way reality is. These discoveries were made. And this is reality."

And so, you get in the situation, in a pandemic, where the science is evolving so fast. We knew nothing at all about the virus when it was first sequenced, besides that it was a Coronavirus based on the genetic sequence. In the weeks that followed, the months, the years that have followed, we learned more exponentially over time about this virus that we knew absolutely nothing about before. And so, in the second month of the pandemic, you know so little. There are so much room for things to change, and so much has changed. You run up in a pandemic with the problem that you do want to respond to what you do know. Even though it's just a little bit, you should try to implement that into social policies and things like that.

So, you get into this contrast between the world of messaging — which, as a scientist, I hate really — that everything, ultimately every discovery gets translated into public health messaging. Yes, maybe that's true. But if we say it like that, a certain subset of people will respond in this way. We don't want that response. The response we want is that people wear masks. And so, how do we deliver the message to get people to wear masks? Now instead of a scientific question — do masks help? Is the virus airborne? How does the virus transmit? What do we know about it, and what do we still not know about it — you get to a desired outcome, which is we want as many people as possible to wear masks as much as possible. How do we communicate it to achieve the behavior?

What you then lose is the actual reality of the science and what you understand. And so, you communicate one thing. Then you have to, two months later, communicate something else. Both times you say, "Science says this is what you have to do." Now nobody knows what's the thing. Because science told me this yesterday, and they tell me this now. Recognizing that science doesn't tell you what to do. Science informs what is a reasonable thing perhaps to do. I think if I could have been in charge — which I thank God I wasn't — I think we could benefit from that. I think we could benefit from giving people the tools they need to understand what we've discovered, and make reasonable decisions about how that should affect their behavior at the personal level. We can provide recommendations. But providing the reasons for those recommendations, I think, in the long term would be really helpful.

It's probably what we can start doing now. Because we can't go back in time, but we can start now to change the way we communicate science to the public. I think, little by little, you can build up trust by trusting people. Trust goes both ways. If you want people to trust you, you have to also trust them. You can't treat people like children who just need to be told what to do. I think you have to share that science is mysterious. It's beautiful. We know lots of things, and what we think we know now might change. That doesn't mean we shouldn't respond to what we think we know now. I think that's a delicate balance. But I think it is a balance that people can manage if we trust them.

Brandon: Well, that's really great. One of the things we've heard when we started this project, we were wondering whether there might be some way to emphasize the beauty of science, that could improve public trust in science, in the sense that a lot of people I think have been put off by a moralistic approach, to a finger-wagging approach, to "This is what you ought to do. We're the scientists. We know better." So, it's that sort of thing.

We asked scientists. The scientists we studied, we asked them, "Do you think that emphasizing the beauty of scientific work can, in some way, increase public trust in science?" Many of them said no, that's really naive. Because people will come to whatever set of facts that you bring them with their own priors. And so, if what you find reinforces those priors, that's great. They'll be happy to support it. And if what you find that threatens them in some way, then no matter how beautiful those facts are, they will reject it.

I've been wondering whether part of the issue is maybe it's not the beauty of facts, considering that especially in this line of work where what you're discovering is changing constantly. You have very provisional understanding that is very rapidly subject to revision. What is beautiful is not so much about fact. But again, understanding, the kind of thing you were talking about. How might we communicate the beauty of understanding which requires it seems some kind of intellectual humility, a willingness to change your mind, even the ability to, I think, appreciate having been wrong? Even Daniel Kahneman, the Nobel Prize winning economist, has the joy of having been wrong. Not because he's masochist, but because there's a deeper truth to appreciate. How do you think we could cultivate this ability to maybe love reality more than one's own opinion, if that's a way of putting it?

Mark: Yeah, I see what those other scientists you've talked to are saying, that it's naive. It's definitely true that if you just show up to somebody with a set of facts and say, "These are the facts, and this is what you have to do," you're wrong. Nobody will respond to that message. Because they say, "Well. Okay. But I have other facts. There's a reason I have —" Any human being you meet, there's a reason they have the opinions they have. They didn't come up with it from nothing. They aren't in a void. In their mind, at least, they aren't in a void of facts, that just needs your facts to come in and then suddenly, they'll change their mind. They have what they think are already facts that have shaped their perception. And so, new facts run into those old ones and are usually rejected if they don't agree and accept it if they do. That's the common process.

I think we always want to be efficient, right? If you just go on TV and proclaim your message to the world, the people who agree with you will agree, and the people who don't agree with you will think you're a lunatic. What I've noticed is, there's real value in having actual conversations with people — which requires a certain amount of humility and requires you being willing to be present as a real scientist, as a person, as a human being who admits that you don't know things, who admits that you were wrong about something two months ago, and take the time to actually listen to somebody, to tell them what you're working on, what you've discovered, why you trust that it's true, what the experiments were if they're curious, to listen to the objections, to listen to the other facts that they have, to respond to those with what you know and why you know it.

Surprisingly, I've been doing a lot of this during the pandemic— just meeting with individual people, or families, or classrooms of 10 students. Some of them fairly hostile environments in terms of the perception of vaccines and things like that. I found really productive conversations can come out of that. Really, I'm convinced that that's the way to change. Not that the goal is to change anything.

If you go into an interaction saying, "My goal is to change your mind because you're wrong," no one will listen to you. You'll never succeed if that's your goal. But if your goal is to share the beautiful thing that you've discovered, and why you're convinced that it's true, and you really go with an attitude of sharing with a person who you care enough about to listen to, I have seen people change their mind, or at least open their mind. I think that that really is what it's going to take, that there won't be a way to publicly proclaim science. But that really at the individual level, in conversation, sharing what science is in a true and authentic way with people. Because you're interested in them as people, not because you want to change their mind. I think that I've seen it being effective. So, it's not just that I think it can be effective. It is. It's the place where I have hope that not all is lost. There's hope. People can change. I can change my mind. And so, there's still hope for this.

Brandon: So, beauty can still save the world, sort of.

Mark: I think so. Yeah, I think so. But we have to share it in the right way. If you reduce science to a set of facts that dictate how you're supposed to behave, there's nothing beautiful about that. Really, there's nothing beautiful about that at all. But if you share what you've discovered, that there's beauty and understanding the world and really understanding it, I think sharing that — yeah, people are receptive.

Brandon: Fantastic. Mark, this has been really great. Absolutely, I'm so grateful for your time. Any other thoughts on this topic that curt you? Anything else you want to share?

Mark: Oh, wow. Is there anything else I want to share? No, it's been a delightful opportunity to get to reflect a little bit on my experience. Because I walk around saying, "This is beautiful. This is beautiful," all the time. "This is a beautiful paper. This is a beautiful experiment." It's really insightful for me as a scientist just to have the chance to reflect and to see, what is it that motivates me? What is it that I want to share with the people I meet about what I do? So, I'm grateful for this work to help even scientists understand better what it is that we're doing, and what our role in the world can be. But otherwise, I think we covered a lot of it. It's been great.

Brandon: Awesome. Where can I direct our listeners and viewers to some of your work, or anything interesting that you'd like to point them to?

Mark: If you want to see my works, specifically, you can go on Google Scholar and type in Mark M. Painter, and you will find the papers I've been part of. Google Scholar is a great place to look for original scientific work. So, if you want to stay focused on science and not opinion pieces, that's a great place to go. Put in whatever you're curious about — SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. You'll get thousands and thousands and thousands of hits. That's where you can find what I've been working on. Honestly, I don't know if it's worth your time to look at it. But if you want to, that's where you can find it.

Brandon: Awesome. Well, thank you, Mark. It's been a pleasure.

Mark: Yeah, thank you so much, Brandon. It's been a pleasure.

If you found this post valuable, please share it. Also please consider supporting this project as a paid subscriber to support the costs associated with this work. You'll receive early access to content and exclusive members-only posts.