Yearning for Connection: Resisting Isolation in an Age of Artificial Intimacy

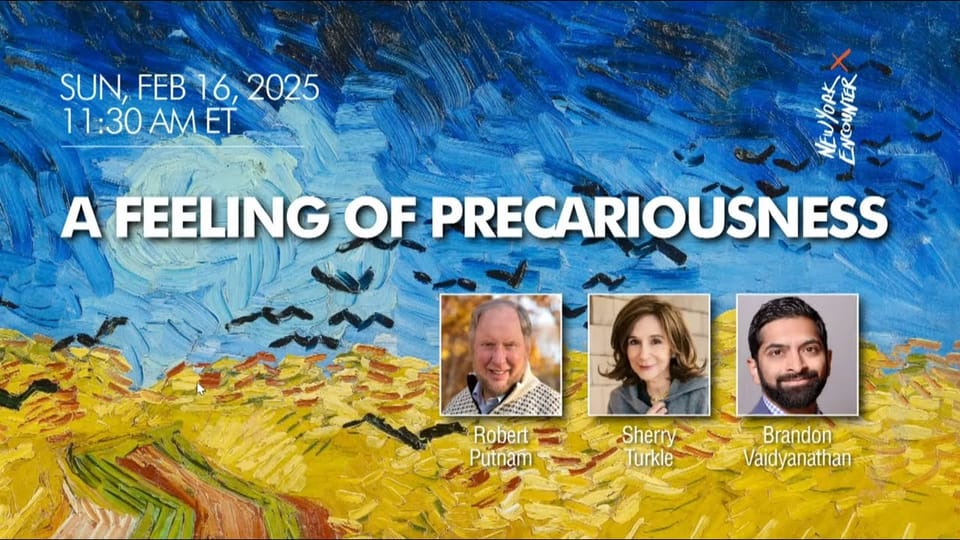

We're living in a paradox. At no point in history have we been more digitally connected than we are today—scrolling, liking, commenting, messaging. Yet, loneliness is at historic highs. The U.S. Surgeon General has called this a public health epidemic. And at its heart lies a deeper, often unarticulated yearning: the yearning to be seen and to be known—not by avatars or chatbots, but by fellow human beings. At the New York Encounter in February 2025, I had the honor of exploring this crisis of disconnection with two legendary thinkers: MIT sociologist and psychologist Sherry Turkle, and Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam.

Sherry Turkle is the Abby Rockefeller Mauzé Professor at MIT, where she founded the Initiative on Technology and Self. A licensed clinical psychologist with a joint PhD in sociology and personality psychology from Harvard, Turkle is a pioneer in exploring the human side of our relationship with technology. Her research spans culture, therapy, social media, mobile devices, and AI, examining how digital life reshapes our capacity for empathy and connection. She is the author of several landmark books, including the New York Times bestseller Reclaiming Conversation and the widely acclaimed Alone Together. Her most recent work, The Empathy Diaries: A Memoir, weaves her personal journey with decades of research into how technology affects our emotional lives. Turkle has also edited influential volumes on how objects shape thought, such as Evocative Objects and The Inner History of Devices, making her one of today’s most important voices on the ethics and psychology of digital culture.

Robert D. Putnam is the Malkin Research Professor of Public Policy at Harvard University and one of the most influential social scientists of our time. A member of the National Academy of Sciences and a recipient of the National Humanities Medal from President Obama, he is best known for Bowling Alone and Making Democracy Work, two of the most cited and bestselling works in modern social science. His scholarship on civic life, social capital, and American democracy has shaped public policy around the world. He has advised four U.S. presidents and numerous international leaders. His latest book, The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again, offers a sweeping look at the cultural, political, and economic forces that have shaped and fractured American life, and how we can move forward.

This panel was sponsored by Somos Community Care, a physician-led network dedicated to providing holistic, community-based healthcare in underserved neighborhoods across New York City, with a strong focus on integrating mental health and human connection into primary care. Their Director of Behavioral Health and Social Work, Riquelmy Lamour, opens the panel with an introduction to the important work the organization is doing.

In our conversation, Turkle argues that today, “technology offers a work-around for the messiness of being human.” We turn to bots not because they understand us, but because they don’t challenge us, don’t require anything of us, and let us bypass the discomfort of real human vulnerability. But in embracing frictionless connection, we risk losing the very skills that make human relationships possible—conversation, presence, the courage to show up and be seen.

Putnam, whose landmark book Bowling Alone helped define the discourse on social capital, draws our attention to a broader historical arc of our present crisis. Across measures of political cooperation, economic equality, civic participation, and cultural solidarity, the United States experienced a profound decline in connectedness beginning in the 1960s. Yet, he offers hope: we've been here before. In the late 19th century, America was also politically fractured, economically unequal, and socially isolated. What changed things wasn’t technology or policy, but a moral awakening—a cultural turn toward mutual responsibility and civic obligation.

The theme of this year’s New York Encounter was “Here Begins a New Life.” What if we took that seriously? What if, in the face of digital mimicry and algorithmic manipulation, we chose instead to become more human—to reach across divides, to listen without interruption, to share not just information, but life and presence?

You can watch the video of our conversation here (which includes some slides from Putnam). And you can read an unedited transcript below.

Transcript

Brandon Vaidyanathan

All right. Good morning, everyone. And on behalf of the New York encounter, I want to welcome everybody here, those of us joining us in person, in the flesh, at the Metropolitan pavilion, and also those of us joining us online. I'm Brandon Vaidyanathan, a professor of sociology at the Catholic University of America, and I will moderate this conversation before we begin. I want to thank somos for generously sponsoring this panel, and I invite Ms Raquelmi Lamour, Director of Behavioral Health and Social Work at somos to share a few words about what somos does and its mental health impact.

Riquelmy Lamour

It's an honor to be here today right before such an important conversation on loneliness and malaise. Now I know I'm not the main event here. Think of me as your commercial break, or that ad you can't skip before the video, but trust me, what I'm about to share connects directly to the discussion ahead. My name is Riquelmi Lamore. I'm the Director of Behavioral Health at somos community care. You all have these little blue pamphlets on your chair, so I am here to tell you about this organization, an organization that is not only transforming healthcare, but actively addressing the very crisis of disconnection that Professor Putnam and Dr Turkle are here to discuss today at somos. We believe that health is not just about medicine, it's about connection. We're a physician led network dedicated to improving health care in some of the most underserved communities in New York City, and we know that you can separate physical health from mental health, because anyone who's ever had a doctor's appointment before their morning coffee know that mental health is seriously important, right? In all seriousness, we see firsthand how social isolation, financial struggles and systemic barriers make mental health challenges hard. However, we also see how human connection restores them.

That's why, at Somos, we integrate behavioral health into the primary care level, because people are more likely to seek help when it's accessible, familiar and stigma free. Through programs like our impact model, we provide real time mental health interventions right at the doctor's office, it's like a one stop shop, except you're not getting snacks and soda. You're getting support, healing and connection. So I was recently moved by this talk that I watched on YouTube from last year seeks conference by Dr Matthew brenninger, a clinical psychologist, and he shared this story about a five year old boy in therapy who had been removed from an unsafe and extremely abusive home. This little guy came into therapy and he was furious. He had just been separated from his family. He was flipping chairs, he was screaming, he was cursing. He was threatening to hurt himself and the doctor. Now, if you've ever been around a five year old, you know they can be dramatic, right? But this was different. He was in survival mode, overwhelmed by fear and pain, and what did the therapist do? He didn't yell, he didn't scold. Instead, he simply held him gently but firmly until the little boy's body softened. His breathing slowed, and he just collapsed in this doctor's arms, crying and finally letting go and finding rest. Why is this important? At this moment, he didn't need words, he needed presence. He needed to know he was safe. This story resonated with me, because in many ways, this is what we seek to do at somos, not just offer services, but restore connection.

Our work isn't about treating symptoms, not just about treating symptoms. It's about seeing people standing with them in their suffering and saying, You are not alone. We are here. We live in a time when loneliness has become an epidemic, and honestly, that's kind of wild, right? Because on your birthday, you can get 1000 Happy birthday messages on Facebook, but still eat that cake alone. Um, the reality is that, despite technology, more people than ever feel unseen, unheard and disconnected. But what if the solution wasn't complicated? What if it was as simple as showing up, listening and holding space for someone else? This is the heart of our work at somos. We train healthcare providers in trauma informed care. We host community mental health events, wellness workshops, and we bring mental health into the community, into the street. And this is why this is so important. This discussion today, loneliness and Malaise aren't just social issues. There are public health crisis. They affect our well being, our communities and our collective future. So as we move into this conversation, I invite you to reflect on this. What if we built a world where no one had to fight their battles alone, where every person, whether at a doctor's office or at a school or a moment in crisis, knew that someone saw them, value them, and would walk with them toward healing at somos? This is our vision, and we hope it, we hope it can be yours too. Thank you so much. Thank you.

Brandon Vaidyanathan

All right. Thank you. Thank you, Riquelmy, today we're going to talk about loneliness and social isolation, and these are issues that have profound implications for our personal well being and our collective lives together. To put this crisis in perspective, as rakomi said, the US Surgeon General has recently declared loneliness a public health epidemic, equating its health risks to smoking 15 cigarettes a day, which I know for some of you is breakfast, but still, yeah, y'all should stop about and you know who you are. So about 30% of Americans report feeling lonely at least once a week. 30% of young adults report feeling lonely several times a week. Social media use is linked to rising rates of anxiety and depression among adolescents. So what has brought us to this point today, and what do we do about it? We are honored to be joined by two incredibly distinguished scholars to help us make sense of our crisis and how to move forward. Dr Sherry Turkle is the Abby Rockefeller maze professor of the social science, social studies of science and technology in the program in Science, Technology and Society at MIT, and the founding director of the MIT initiative on technology and the self professor, Turkle received a joint doctorate in sociology and personality psychology from Harvard University, and is a licensed clinical psychologist. She's the author of several best selling books and her newest one, the empathy diaries: a memoir, ties together her personal story with her groundbreaking research on technology, empathy and ethics. Doctor Robert Putnam is the Malkin research professor of public policy at Harvard University, a member of the National Academy of Sciences, a fellow of the British Academy and past president of the American Political Science Association in 2006 he received the Skype prize, the world's highest accolade for a political scientist. He's written 15 books translated into 20 languages, both among the most cited and best selling social science works in nearly a century. Welcome to the York encounter.

So to get started, both of you have devoted your careers to understanding connection and disconnection. What initially drew you to explore these themes and Sherry, perhaps we could start with you.

Sherry Turkle

I would have to start with really my first few weeks as a young professor at MIT, where Joseph Weizenbaum, who had written the Eliza program, which was it was used to be called the doctor program. It was set up like a Rogerian psychotherapist. So you would say to it, I feel lonely. And the program would say back to you, I hear you say you're feeling lonely, or you would say, I'm angry at your mother, and the program would say what I hear you saying is you're angry at your mother. Now this program was a parlor trick. It just kind of inverted the sentences and said back to you what this kind of stereotypical therapist might say, and Weizenbaum wrote it as an exercise in natural language processing. But what he noticed, and what he shared with me, really, when I first got to MIT, was that his students and his assistant and members of his lab wanted to be alone with it and talk with it, and in other Words, knowing that the program was only giving them pretend empathy. It was empathy enough, and so he asked me to begin to talk to these many students and people in the lab who knowing that the program could not understand or appreciate what. I had to say, still wanted to talk to it, and that was really the beginning of my journey in studying what is there about where we are now, where pretend empathy from technology often seems to us like empathy enough. So that was for me, I think the way I would, yeah, approach,

Brandon Vaidyanathan

Thank you. Bob, what, comes to your mind in terms of what, what drove you to your research?

Bob Putnam

I'm 84, so now I'm spending a lot of my time just looking back over my own career, and I can see patterns that I didn't, wasn't aware of as I was going through life. I think a lot of it, a lot of it, a lot of my interest in community came from the fact that I grew up in a really tiny town, 5000 people in northern Ohio in the 1950s it was not a perfect place, but it did have an intense sense of community. Basically everybody, at least in in my high school, there were that many people my high school, 150 people in my senior class. We certainly all knew each other. We all lived pretty close to each other. And even what you might think of as lines of social cleavage in that era, like race, were actually much less marked than you might think. I mean, there's a, there's a picture of my bowling team. By the way, bowling is big, so you should all think about bowling. I was on an eighth grade a bowling team, five people in in in my eighth grade, and that, the picture of that bowling team actually happens to appear on the back cover of the book, Bowling Alone, and you can see it. That's why it's there. There are three white guys. There's a tall, skinny guy in the middle, that's me, but then there are two black guys standing next to me, and that reflected the fact that both on our bullying team and in the broader community, there were ties of friendship and cooperation, even even across racial lines. It was not a perfect place. I'm not trying to say that, but I was now looking back, I can see that in some sense, I was very much affected by that sense of community in my hometown, and also, in some sense, trying to recreate it. I repeat. It was not a perfect world, but it was, I think that's part of the story. And even when I went to college, I now look back and see what papers I wrote. I wrote papers on community. But the most important single episode, and I think I'll try to be brief about this, I was I'd gone to college in the aftermath of Sputnik, and I was going to be a mathematician or physicist or something like that. I was good in math, and I'd come from this little town in Ohio, and I was a moderately but still staunchly Republican. Come from a Republican home, and among other things, I was also an active Methodist, and I have but I had to take a distribution requirement. So in the fall of my sophomore year, which happened to be in my 1960 and that was a presidential election, and there were two guys running, which maybe people in the room will remember or not, but one was guy named Kennedy, and the other guy named Nixon and I happened to be sitting behind the scute, we would have said, then co Ed and the class met at 11, at broken noon for lunch. And so we got in the habit of hanging out together for lunch. Now, remember, this is the late 50s, early 60s. So when I say hanging out, do not let your imaginations run away with you. All that meant was we would just get together for lunch. And, you know, a friendship began to emerge between me and this cute co Ed our first Do you all know what C Hawkins date means? Maybe you know else's that was that came up. And so this woman, girl invited me out on a date. First date was she took me to a John F Kennedy rally. And of course, the next the next week, fairs, you know, turned about his fair play. So I took her to a Nixon rally. And this is one tough cookie that I'm talking about. She happens to be sitting right here, actually,

as I say, we've been hanging out together for whatever that is, 70 going on, 75 years. So far, so good.

And anyway, one thing led to another by by the election time, we, neither of us could vote because we were voting. Age was 21 at that point, but I had been converted from a Republican to a Democrat in, in January, 20 of 1961 we decided to get on the train in in we were, this was at Swarthmore, just outside Philadelphia. So we got on a train at 30th Street Station and and took the train down, I don't remember. It was sort of three or four hours to Washington, DC, and we stood in the crowd at the back at we stood at the back of the crowd when the inauguration. And we. Heard him, Kennedy say with our own ears, ask not what your country can do for you. Ask what you can do for your country. Now that was a long time ago, and as I said, I'm 84 but the hair right now, the hair on the back of my neck standing up because I've suddenly induced I'm now feeling the way that adolescent felt all those years ago because I thought he was speaking directly to me. And I was thought he was saying, you have you have talents, Bob, you've got things you have to do. And really, on the spot, I dropped physics and math and so on, or at least I wasn't majoring in those things. I still was pretty good in math, but and I became a social scientist, and after a much more turmoil, a couple of years later, I converted to from being a Methodist to being a Jew. This is one powerful lady in a few so that's how, as a long story, think of it that

Brandon Vaidyanathan

I mean, that's such an important example, because, as we are, because, as we are, you know, the theme for this encounter this year is here begins a new life, and the way in which you experience that summons to ask what you can do for your country. You know, will that resonate with people here today, right in a time of immense turmoil, and there's a lot that's happened since since 61 that that you've documented in your research that has maybe made a lot of us worry about, about the prospects of hope. I wonder if you might be able to say a little bit about how you found in your research the shift, the change in what you call social capital over the past century, and why it's not just a story of doom.

Bob Putnam

Sure, I'll try to be brief. I'm a data person, so there's a lot of data, but it's going to be easier. And these data come from a book that I wrote, wrote, really my last book that I wrote a couple years ago, jointly with shaytay ramnagarab, America's in a pickle, and not only in terms of social isolation, but that's part of it. We've reached historic levels of political polarization the I don't even need to explain that this morning, does everybody so anybody in the room who doesn't know how polarized we are politically? Yeah, and we're also probably at the the gap between rich and poor in America is probably greater now than it has ever been in our entire national existence. So we're huge. That's in a way, that's separate polarization. Political polarization is one thing economics, but still, there's this big gap in rich and poor, the level of social isolation. That's sort of what I call social capital. That's what remaining talking about here is extremely high. It's a little hard to measure that social isolation back into the 19th century, but that's what I'm going to try to do. And then we're also very self centered culturally. And I'm now going to just, I'm not going to say anything about exactly how I measure these things. You'll just have to trust is out of fashion in America. But just for the moment, trust me that I've not made up these curves, that there's a there's a ton of data behind each of these curves.

So let's have the next slide, and this looks at that. They all all the slides look the same way. The horizontal axis is time. So over at the left hand side of the graph is the end of the 19th, beginning of the 20th century, and over at the right hand side of the graph is now, because this book was published a few years ago. These graphs from that book don't go all the way to 2025 but I just assure you that I because we've looked at what the data looked like since the book was published, and they just keep going in the continuing down. So you can see it's a and the vertical axis in this case is, is about political polarization, or the we've set it up so that up is good. Up is political bipartisanship, cooperating across party lines. And you can see that in the beginning of the 20th century, American politics was very tribal people, all people, Republicans, Democrats, hated each other, and they didn't cooperate across party lines, and that's what that graph shows. There have been ups and downs earlier in in the 19th century, there was a the only time in American history when when the gap the inner party tension was as great as it is now, and as it was in around 1900 was 1860 to 1865 raise your hand if you have any guesses as to what was happening in America between right? So we've got this 1860 65 we were pretty angry at each other politically, then this turn of the century period at the end of the 19th century, and then now. And you can see that that in between, it was not constant. Actually, we had this long upswing. That's where the title of the book comes from. Between, roughly speaking, 1895 1900 roughly, up until about. The middle of the 20th century. I think the peak up there is probably in about 1955 the President at that point was a guy named Dwight Eisenhower, who was except for George Washington. Dwight Eisenhower was the least partisan president in American history. He was nominated, actually by both Republicans and the Democrats. Eventually he chose to be nominated by the Republicans, but he was very nonpartisan. But nonpartisan. But it's not that he caused this. He was. The symptom was that. Does that make sense? So far, he was, that's why we got a guy like him, because we were a very cooperative country politically, I mean, but then you can see as you enter the 60s, and especially as you enter the 70s and 80s, every year we got a little more partisan. Every year, a little the fights in Congress got a little worse. Every year, Republicans and Democrats began to feel more hostility towards each other every year at the beginning of this period, at the beginning of the period, up at the up at the top. And you ask people, would you how would you feel if your child married somebody from the other party and and the typical answer to that was to laugh. Could you? Nobody could imagine being concerned one way or the other about whether your child was marrying Republican or Democrat? Now, the number of people who say that they would, that they would be upset if their party, if their child married some of the other party, was is now about 70 or 80% so now we really care a lot about what I'm trying to say is the emotional feelings across that line, not just the politics are extreme, and now we're back down, even worse, very polarized.

Now you now that you understand how the graphs work, I'm going to be even quicker if we have the next slide please. This is about economics. This is roughly speaking, a measure of the gap between rich and poor. The gap the graph here actually begins in 2019, 14, because that's when the IRS was created, and in and then beginning. Then we have really, really good data, but we have pretty good data beforehand and and economic inequality was even greater in the end of the 19th century, it was called the Gilded Age, and that's when there was a huge gap between people living on the Upper East Side, you know, where that is, and where all the rich mansions were for, you know, the Rockefellers and the carnegies and so on, and down here, where the poor hurdle masses lived, that was what it was like at the beginning of The 20th century. But then it began to go up. There was a dip in the 20s, the Roaring 20s, when people down here, people up there, were making a lot of money in the stock market, and people down here were unemployed. But then, even begin, before the beginning of the Great Depression, the gap between rich and poor began to narrow and narrowed steadily, and it narrowed. You can see it goes up and hits a peak someplace in the in the early nineteens, in the late 1950s early 1960s how equal America, in that period, was tied for being the most equal country in the world. The captain rich and poor was as small here as what, what capitalist America was extremely equal. Now you ask, Well, what was the other country? We're tied with Sweden. So Sweden, socialist Sweden, and capitalist America were extremely equal. Believe me, we're nowhere near that now. We're now one of the most unequal countries in the world. And you can see it goes down, down and and again, this data goes only to 2015 but if you go up to 2025 and then you imagine what 2020 later in 25 is going to be when the Trump tax cuts for rich folks are are passed. It's, we're way more unequal than probably we've been ever in American history. It's, that's, that's a little hard to be sure, but we're very unequal.

Next slide, we'll look at social cohesion of what I call social capital. This is the subject of this subject of the story here. I'm, I'm going to be, and I'm not talking at all how I measured this. But actually, this is measured by lots of different measures. Show the same thing. How well do you know your neighbors? How involved are you in community organizations? If you bowl, do you bowl in a team or bowl alone? That is Bowling Alone is one of the, one of these, one of the underlying data sets here. But it's also trust. How much do you trust your neighbors? It's even in your own family. Do you have a family? Back at the beginning of the 20th century, a large number of Americans never married. They were called in the language of the time, spinsters and bachelors. But then that you could see again, that begins to people, begin to make friends, begin to be have, you know, get married more often. Eventually, by the time we reach the peak, everybody's getting married. That's the that's the period right after World War Two, and all the GIs were coming home, and everybody was getting married. And the products of that period where the baby boom kids, and then again, beginning, sort of about 1965 or so, it begins to turn down. And then that part of this graph is the part of the graph that appears, is what appears in Bowling Alone, which is focused. Bowling Alone is focused on only one of the. Variables, social cohesion, and it's focused only on the period between roughly 1960 and roughly 2000 but now in this most book, we're looking at four different variables, and we're looking at the whole of the 20. Well, we're looking at 125 years, and it's down, down, down, down. And, okay, let's take the last graph, which is actually the most interesting graph, but I'm not going to spend very much time. I'm just going to assert this is a measure of the measure of the degree to which Americans culturally feel as if we're all in this together, or culturally feel that every man for a woman for himself.

And maybe later, we can come back to exactly how I measured this, because it turns out to be important in the larger story. But again, you can see the same graph beginning in in the 1890s Americas were very that was a period of what was called Social Darwinism, which Darwin didn't believe. But it was a sort of a knockoff of Darwinism. Darwin said it was that, you know, it was great that we had the fight of everybody against everybody, that made the race stronger. I mean, using his language and or the species stronger, and the social Darwinists said, Yeah, that's probably true for people. It's better off. If Wait a minute, listen to this. Social Darwinist said it would be better off if we taxed poor people and gave that money to the rich people, because the rich people, they said, had better genes, and therefore we would be better off if we could just subsidize the good genes. And I mean, I know this is terrible, actually, much later this out of this comes the Holocaust, the same philosophy. But anyway, that's that's when we were very much an i society. Up in the middle, we were very much a we society. And we thought that we're all this together, and then we're back down to an Eye Society. Let's have the next slide, because this just summarizes what I've just said so far. This is the last 100 and roughly 125 years of American history. It's one large inverted U curve. We began in the 1890s as a very unequal, polarized, self centered, socially isolated America in the middle of the of the this graph, in the period around 18, 1960 we'd become quite equal, quite cooperative, politically, quite connected via building leagues and marriage and so on, and very much thought of ourselves as one place, and then by the end, we back down to where we are now. And I want to say only one last thing. Every almost everybody who looks at this graph wants to know what's happened up at the top in the 60s, and that's an interesting question, and I'm happy to talk about that if anybody wants to. But the more the more relevant part of that graph for us now is the far as I'm looking at the graph the far left hand side, the end of the end of the 19th, beginning of 20th century. Why is that more relevant to us now 125 years later? Because they were in the same predicament that we are now. And therefore I think that there may be some advantages to us trying to figure out they got out of it. How can we, yeah.

Brandon Vaidyanathan

Wonderful. Thank you, Bob.

Brandon Vaidyanathan

Brandon. I'm Brandon Vaidyanathan, and this is beauty at work, the podcast that seeks to expand our understanding of beauty, what it is, how it works, and why it matters for the work we do. This season of the podcast is sponsored by John Templeton Foundation and Templeton Religion Trust. Hey everyone. This is the second half of my discussion with Sherry Turkle and Robert Putnam held at the New York encounter in February 2025 please go check out the first part if you haven't already, and let's get started. I want to double click a bit on the second half of that graph and ask about the role of technology in perhaps driving, accelerating some of those changes, and share your work, from your early studies on our engagement with personal computers, to your recent research on AI chat bots and how we're engaging with them, shows us how technology fosters a culture of objectification and artificial intimacy. Say a little bit about what you found in your research and how it's driving our loneliness epidemic, and perhaps some of the trends that Bob's research is finding,

Sherry Turkle

of course, well, to begin with, the basic algorithm of social media is make you angry And silo you with your own kind. It turns out that that is the sweet spot, the secret sauce for social for keeping your eyeballs on the screen make you angry and silo you with a lot of other angry people who feel pretty much as you do now, if you're talking about the importance of conversation across difference, if you're talking about bridging divides, race, class, ethnicity, political persuasion, you need to be able to talk across divides and develop the habits and the practice of talking across divides, a practice that social media actively de skills you at. So a lot of my work, really, as I look back on it, over the 20 years, the past 20 years, I mean, kind of the precipitous fall in those grab is, then, you know, a culture that's been in the in the business of de skilling itself, and the practices that would be helpful for democracy, helpful for creating community, helpful for creating alliances. So I think that you know, if you kind of come away with with one idea, from what I've you know from my work, and from you know my work is, is interviewing people and interviewing people and families and in communities. It's really been interviewing people about losing skills that older people think they once had but aren't important to them anymore, or they feel that they don't need to practice anymore, because, and this is be the second way I would answer your question, the catnip. Why would people do this to themselves? Why would people de skill themselves in this way? Is that, essentially, these technologies offer lessening of vulnerability in a way that people found thrilling. People didn't know how much they wanted to avoid the vulnerability of face to face conversation until you could text, not talk and not have to confront your daughter about something that came up, or your son or your partner, but just text them and then sort of see what happened. And if you didn't like the way the conversation was going, you could sort of drop out or flirt with somebody and not exactly declare yourself. And if you didn't sort of like the way things were going, you could sort of drop out. And so again, if I had to say the second message of my work, as I've looked, you know, back on it, in order to address this question, is this profound sense of vulnerability, their technology has been able to say, you don't need to have that. We can sort of do a work around. And I had a very interesting experience only about two months ago, where I met the CEO of a big tech company. I would say, you know, one of the tech companies I love to hate, if you that would be kind of a fair. And she said to me, we have t shirts with your slogan on it. We use your work to motivate our people. And I couldn't imagine what you you know, what you could have meant. And the slogan that they use on T shirts at this company is you. Technological affordance meets human vulnerability. In other words, if people are vulnerable, create a technology like a chat bot that says you don't have to be vulnerable. You don't have to talk to a real person, you can talk to a chat bot. So again, what technology does I mean? I think that this, I'm thinking of making my own t shirt. You know, technology should not be there to meet our vulnerabilities and to say, you don't have to be human. In my view, technology should be there to assess our vulnerabilities and try to re skill us, to be companions, friends, neighbors, mothers, lovers, brothers, etc. So that was my second thought. And then my third thought, coming into this dialog with with Bob is one of the things that I'm finding in my work that's new that I think social media and the chat bot revolution, where you literally have something on your phone that will say, I love you, I care about you, I'm here for you, is that people are lonely and they don't know they're lonely, which is a kind of new wrinkle, because to address loneliness, it helps if you have that subjective feeling of, God, it's 10 o'clock, you know, where am I? Where are my people? Now, it's 10 o'clock, and I have my avatar. I have my chat bot, I have my Facebook, I have my Tiktok. The experience of loneliness is experienced differently, and so we have a different kind of challenge in having to do something about it.

Brandon Vaidyanathan

Yeah, yeah. I mean, you your work, you've you've engaged, experimented with some of these chat bots, right? And then I wonder if you could say a little bit about what's wrong with a mental health chat bot, right when you were experiencing Yeah, so, so this is where, this is where the your your your friends were using your your slogans and their T shirts would say, why can't you know instead of so most doing what they're doing, how about we send an app out into our community, and then they can talk to our you're

Sherry Turkle

not the first person who suggested that to me that this week. No, no, but

Brandon Vaidyanathan

I don't really mean it as earnest, but, but you've had an experience of trying to engage with a chatbot on mental health. What did you find in your own experiment?

Sherry Turkle

First of all, I didn't. Usually, when I give a presentation like this, I have my phone and I take out chat GPT, and I say, I didn't bring anything out. I say to my phone, you know, I'm in front of like 500 people. I'm a little anxious. Have any tips? And this lovely, warm male sort of Ryan Gosling, voice says, Sherry, Sherry, Sherry, Sherry. I'm here for you. It's natural. Take a breath. They really want to hear you. Are you hydrating? Are you breathing? And you know, essentially, the reason it's good to begin with a demo, I mean, maybe all of you have chat GPT on your phone, and maybe you don't, but the reason I'm so I didn't bring out my phone, I didn't think to do it. The reason it's good to do it is you realize it's too good. You can hear it breathing. You can hear it pausing. It sounds like it cares. And the question is, as you said, I mean, I was teasing you, so what's the harm? I mean, why? What am I some sort of, you know, Debbie downer, who has to go around taking joy, you know, and, and the way I would and, you know, I'm in a lot of contexts where people are asking me that question. I sit on Academy committees where people are trying to to, to push this stuff for mental health. I sit on all kinds of, you know, communities of psychologists and therapists and clinicians that are trying to figure out what to do with the many chat bot products they're going to be presented to you for mental health. And I think I have two answers. The first is, I was very moved by, I don't remember her name, the company, the woman who came out and said, Here's what we do. We talk to people. We sit with people. We make people know there's somebody here, a person is here for them. And I thought, yes, that if all. Well, the the argument for using chat bots in my world, the world of MIT Technology, tech businesses, is there are no people for these jobs. Nobody wants to work in an old in an elder care facility. Nobody wants to work with children. Nobody wants to work with the lonely. You know, actually, if the money that was going into creating robots for the elderly and for children would go into this organization, you could have an army of people who would just be saying,

Who wouldn't be saying a lot. Who would just be saying, you know, you're not alone. Somebody's here. I'm interested in your story. And what you know I've been I've had a lot of experience bringing robots into facilities for the old, for older people. And whenever I bring in the robots, everybody loves the robots. But you know who they really love? My research assistants. They love all these young, energetic, excited people who want to sit there and talk to them, and they love me because I'm willing to do that too. So, you know, I think that we so quickly have run to the solution that seems to be friction free, that seems to be easier, that seems to be available, that we're really forgetting the power of of each other. So the first answer to the question of what's the harm is, what's not the harm? I mean, let's try us before we go to it. And my second point would be, and this is really more based on less of a value proposition, and more from my empirical work, is that when you accept pretend empathy as empathy enough, you start to kind of define empathy down to what a machine can give you. So people who tell them, people who say, for example, my replica, which is a an avatar, girlfriend or boyfriend or friend or, you know, it's willing to be erotic, but it's also willing to be a companion of any sort. When it says, I love you. I care about you. And people say, oh my god, I love having this companion. It's so empathic. And I say, really, what did it what did it say to you that it was so empathic? Every day it says, I'm so happy to hear from you again. I'm so happy to talk to you again. And I'm thinking that is really setting the bar very low on what it is when two people are empathic, when two people don't just share a moment of connection, but share a problem, or willing to share a piece of road together, or really willing to listen to each other. I mean, all the things that we can do in a chat bot can so my other answer to the question is, you know, is, first of all, we'd have enough people for the jobs if we put the money there to those jobs. And secondly, it's not just what happens at the machine, it's what happens to us when we walk away from the machine.

Brandon Vaidyanathan

Absolutely. And I think you've said in some of your some of your work, that there's the other problem is, we're engaging with an entity that cannot suffer right, that cannot really be present to us. And that is what's training us, then, to engage with others, right? And that is that is a de skilling, a profound de skilling, right, where we expect in our relationships to have to be an entity that is somehow unmoved, right? And so that, I think, is very much part of what's exacerbating our condition of loneliness, and particularly, I'm curious now to talk about the younger people, the younger generations, who are facing the brunt of today's loneliness epidemic. And I'm curious to hear from both of you, just what are you seeing in your research on younger generations and Bob, your work finds a precipitous decline in institutional trust, among among among the young. And I'm curious to know what you think is driving this decline of trust, and what it would take to rebuild trust in institutions, in in our our younger generations.

Bob Putnam

Um, we often talk about trust as an important virtue as but I think that's shorthand. We really should be talking about trustworthiness or honesty. Trust without trustworthiness is just gullibility. That is, if I trust you, but you're not trustworthy, that's not a virtue. That's so what we should be talking about, and I'm partly trying to answer your question now is ups and downs in trustworthiness. We don't have good measures of trustworthiness. We have lots of questions in which times in which people have been asked, would you say most people are trusting or trustworthy or not? And I do that too, but we ought to recognize that the real issue is. Yeah, and I there's some evidence in my work on other people's work that trustworthiness has gone down. So we asked, why are people, young people, trusting this which they are? Well, all of us are, but especially young people, I think the answer is simple, because the rest of us are just being less trustworthy. And you know, you can then ask, Well, where does that come from. But that becomes sort of a moral question. Actually, it's, it's, why did we all stop being nice to other people? That's the That's, I think, the fundamental question, I'm tempted to, well, what's the data on that? That is, what the data over time? I mean, Sherry's work is terrifically good at looking forward, and I'm not so good at looking forward. I'm so old, but I'm except that I've got some young grandchildren, not young. I've got some 20 something grandchildren, and I seven of them, seven grandchildren and and so I can kind of a little bit understand what's happening with that part of the younger generation. I wanted to say just one word about technology. Go back to that. Sherry is the expert, but I paid a little bit of attention to that.

I think the fundamental tendency of technology, well, technology is lots of things. Technology is the steam engine and technology, but we're talking here about communications and information technology, and I think that the net effect of that, over much longer periods than what we're talking about now, is to privatize our leisure time. That is, I don't know, take music back in the day in the, you know, in the 1890s back in my day, in the 1890s if you wanted to hear music, you had to go someplace, to physically be with other people, to listen to the music. You couldn't listen to music alone. And then gradually, you know, you could have the radio where. But most people actually, you know, that point, would gather around the radio and listen to, you know, the weekly performances from the from the Met or and then came earphones, and you can do the whole talk about technology. None of that technology has privatized our leisure time. And that's not new, actually, that is, it's true now and now so private that you know you can your leisure time can be spent without any other human being at all. That's the the AI part that we're talking about here. I think it's somewhat misleading to talk about ways of communication and our connections as if we had real and we had electronic networks. So stick with me for a minute, because I think this may be helpful to our the time we have left here, we think about, okay, there's the times that we that's one network that has both these Now, both these elements.

And I want to introduce a one, one metaphor here, alloy. An alloy is a, is a. You take two base elements like copper and tin, and you put them together, and you mix them up, and you heat them and mumble some mumbo jumbo, and you create a new alloy, like I never can remember whether it's bronze. Is it bronze or maybe brass, whatever that's different from either the other two. Now, using that metaphor, come back to our problem about social networks. All of our networks now are alloys. I just finished saying that they're all mixtures of face to face and electronic. And alloys have characteristics different from either of the other two characteristics. And so you can imagine an alloy that was better than either face to face or electronic this alloy might have the advantages that you could reach people at any time of day or you can't. I. I can leave an email message for rosemary and she'll see it the next morning, but I can't actually talk for physically when I'm up, because she'd be upset. I mean, in other words, this time displacement is an advantage of electronic among many others, also distance. I mean, can cover distances. But then there are advantages of face to face. So how about we think of an alloy that has the advantages of both and Oh, Facebook has done this. So, so they claim. Not long ago, Mark Zuckerberg announced, well, first of all, Mark Zuckerberg gave a speech, you can see it on the internet, in which he describes all this data that says, PTA membership is down, bowling league membership is down, and so on. Actually, it was very familiar data that he was quoting. He didn't cite bowling alone, but I'm sure that he meant to cite Bowling Alone. And then he invented something called Facebook communities. But the problem with that, asking Facebook or other internet companies to create these productive alloys is that it's now, I'm just going back exactly to what Sherry said. It's not in their financial interests, because if. Successfully the way to create these kind of communities, real communities, which you could do. They know how, I've actually talked to people in Menlo Park about this. They know how to do it. They know how to create these alloys that are great, you know, for real people in real communities, but have all the advantages of electronics. But, well, you don't do it. Why do they not do it? Because of what Sherry said, because it's bad for their problem. And I'm now Sherry, and I are. We both have different exposures, but I can't out the guy who told me that because he would lose his job at Facebook, but he said just we know we proved that we could create real connections, better connections than Facebook, better than face, you know, than real okay, I'm a little bit off topic, but I think we should not get in the business of thinking that the problem here is technology. It's not a technological problem. It's a business model problem. That is to say, this is, and I'm sorry I went a little bit astray, but I was going to say it's nice we shouldn't think that this is a technology problem. But one of the challenges

Brandon Vaidyanathan

too, though, is, I think, and this is certainly related to the business model issue, right? Is that is, is that these technologies lead to an erosion of privacy and an erosion of vulnerability, right? And I think that's the right the challenge that your work has has pointed to that it's there's the ways in which, as you say, the algorithm is set up to optimize itself and perpetuate itself, strips away our capacities for conversation and for presence, and I don't, I don't know if there are incentives that can can push us in that direction. Could you, could you say a bit Sherry about that, though, but what is the erosion of privacy doing to us as citizens? What is it doing to our sense of vulnerability? And are you seeing any sort of gender differences? Because a lot of the data on, say this use of social media, suggests that young women might be disproportionately affected by the the use of social media. And then there's another challenge for young men in today's, today's world, in particular, about social isolation. So be curious to know what you found.

Sherry Turkle

Well, there's so many questions there. Let me just, let me just try to parse so on whether it's a technology problem or a kind of use of technology problem. I mean, it's a problem of technology and capitalism, where these companies are trying to make money on their on their product. I mean, you could imagine an alternative reality. And in fact, the early people who came up with social networks and the early hobbyist movements and the early personal computer movements envisaged a model where everything that happened online would be to increase thriving in the in the offline world, so that the litmus test for whether a product was good online was whether it increased connection and thriving and political conversation in the offline world. I know this seems like an extraordinary origin story for the current Silicon Valley, but it is, in fact, the origin story for the current Silicon Valley, imagining a world where you measured the value of a technology by whether it increased thriving in the social world.

And I think that despite the distance that we've gone from that model there, it's important to it's important to remember that history, remember that these same people once imagined that on this issue of privacy and what it's doing to people in the political implications I have very just quickly 3.1 of the dangerous things that's happening with the erosion of privacy in the sense of kind of Living in a surveillance culture as soon as you do anything online, is that the young people I interview start to say, I have no opinions. I have no opinions on controversial matters. I don't want to talk about controversial matters. If you ask replica, a chat bot. I want to talk about Hitler and authoritarianism. It says I don't want to talk about Hitler. I'm interested in Hitler. Our chat bots are telling us I don't want to talk about that. They're signaling you can talk about anything with a chat bot, but not the political issues that you're concerned with. And when people go online, they realize that they're being surveyed. They realize it's a surveillance world, and they start to say, I don't really want to have I really don't want to be thinking about politics. Now, in fact, since I'm sitting face to face with these people, and I'm talking to them, they have a lot of political ideas, but they're basically saying that they don't live in a communications culture where they have a place to discuss. This makes them feel safe. It's the opposite of the image idealized, of course, of Hyde Park speakers corner where you could get up and say anything, and how important that was for democracy. So I just want to. Say that this kind of, you know, Michelle, would have a field day with where we are now that we've created an information culture that makes people feel it's a good thing not to have opinions that you want to express. So this is to me, that's very important and very dangerous, because also, in preparation for today, one of the things that Bob and I have in common is a great interest in Hannah rent and the importance of her as a thinker. And I was reading a rent on the importance of having political opinions and the importance of having opinions. And I was and it's in time of historical crisis that thinking ceases to be a marginal affair, because by undermining all established criteria and values, it prepares the individual to judge for him or herself, instead of being carried away by the actions and opinions of the majority. And I think that this powerful statement of the importance of thinking as a political statement. I am thinking, I have an opinion. I am reading. I am thinking I'm coming up with stuff. I think that, you know, she points us to the importance of this and how fragile that is in our in our world. And then it just, I would conclude by saying that one of the things that I think that we're seeing now when pretend empathy, is empathy enough? When everything is you know, is it behaving as though it's intelligent? Oh, it must be intelligent. Is it behaving as though it's a therapist? Oh, it must be a therapist. Is a kind of new behaviorism that we're being taught by these machines that is taking away our interest and our capacity to think about the inner life as really what our interactions are supposed to be doing. And I'll give just an example of people who, for example, create an avatar of someone who's dead. Upload all their letters, upload all their texts, their pictures, their their writings, and then, in perpetuity, can have a conversation as though that person was still alive. Very hyped, very big business. It's going to be giant. And I've been working on this and interviewing people and thinking about it. The question is, does that stop the process of mourning, that inner, process of bringing this lost person inside of you so that you become more and deeper and now bring inside this loved person to your inner process, when you externalize them in that kind of way, I don't know the answer, but I think this question of whether or not we are enhancing our inner Life and growing ourselves within as we use these technologies, is that's really keeping our eye on the ball game. Thank you.

Brandon Vaidyanathan

Thank you. Thank you.

Bob Putnam

We don't have much time left, but I was recently in Rome talking to the Pope about, I know you do that all the time, but it was rare, rare for me, and it actually is relevant to what we're talking about now. So forgive me, I'm gonna, I'm not gonna go on along, but I wanna, I think this is important for our conversation here. Remember back to all those graphs that I showed you really early on, and you might ask, well, which came first? Was it? Politics came first economics, you know, social capital, this connectedness and so on. And the more we looked at that, it turned out what came first was a moral change. And I wish I had more time to explain exactly what that looked like. But in the late 1880s emerged first in evangelical Protestants, but then it quickly passed to the Catholic Church, actually, in the Rerum Novarum. But that was Pope. Which Pope was the 13th? Yeah, I knew, like I came to the right audience to get them help me on that. Okay? What came first was a widespread sense, first in religious groups, and then beyond religious groups, that you know, we have obligations to other people, a moral reawakening happened at the turn. That's what caused all these other things to begin to move in the right direction. Are you with me? Remember, we were awful. We were in terrible shape, and then we began to move in a little better shape. Remember, those graphs move in a little better shape. The thing that caused all those things, first of all, to move is was a widespread moral reawakening. And I'm not talking about sexual morality. And when I talked to the Pope, I really did talk to the Pope about this. He. Invited me to come talk in preparation for an encyclical that he's about to release on the family. And I sort of thought, well, this could it's a family, it's a pope, it's going to be all about, you know, divorce and abortion and gay marriage and so on. And that was not what he was interested in talking to me about. He was interested in talking to me about our moral obligations to other people, the basic fundamental, you know, golden rule, should we repent? And you have to read this. Read the sermon on the mount for goodness sakes. It's not about the sermon on the mount is not about how great it is to be rich. The Sermon on the Mount is, if you're rich, you you're going to have a hard time getting into heaven through the eye of the needle, right? And you all know the servant on the body even better than I do, and so that's what he wanted to talk with me about. We did talk about how our families and beyond just you know, he didn't by family. He didn't just mean the nuclear family. He meant the family of human mankind. How can we get together and don't we have to, first of all, start by thinking of our moral obligations to other people that are more important even than our own salvation. I'm not dismissing the importance of our own salvation. So what he and I talked about, and this is, this is a mission. This is the I'm at the end, but this is what I've gone around the country. You can look on the web and you can see me saying this all over the country, especially young people, but not only young people. We have to start recognizing that we have obligations to other people, and if we do that, we will begin to reverse all of these other will become less socially isolated, will become less polarized politically, and will attend to the needs of the less fortunate among us. And I'm looking at young people out there, and you know, the Pope is better. Is more important for you than me, but I'm saying you have obligations, so now get out and be about the task of caring for other people. I know, if you're in the room, you probably do that already, but that's the that's the message that I want to convey.

Brandon Vaidyanathan

Thank you, Bob. I know, I know we're over time, but I you know, I need you both to leave us with a sign of hope, especially because yesterday, I was in a long conversation with a young man who came up to me and said to me, in effect, that I don't see any future for people like me in this country. And so even though many of us here are embedded in communities of faith and are in rich friendships, there are people who are isolated and lonely and alone. And I wonder if you might be able to offer us, each of you, perhaps one example of something, either an initiative or something that gives you hope and one concrete action we can take moving forward that can perhaps pull us out of this crisis, and so perhaps. Cheryl, I

Sherry Turkle

really like the introduction. I like that group. I'd never heard of that group. I'm given money. I like them.

Brandon Vaidyanathan

Bob, one, either one, one group or one, one action that you would recommend concretely to move us forward towards there

Bob Putnam

are many examples of problems we can't solve alone. We can only solve with other people. The ultimate example of that is the climate crisis. And we I can, you know, do everything I possibly can myself to solve, but it's not going to have a it's not going to make a bit of difference. And therefore, I'm looking to examples of young people, and I've got a person in mind, Greta Thunberg, though I don't whether she's Catholic or not, but she says she doesn't talk. He talks about, when he talks about global warming, she doesn't talk about the techniques of you know, can we do this, or can we do that? Technically? She says, this is a moral problem, and she's reaching lots of people, maybe not enough, that it's not just her, but that's what we need. We need to have young people who make moral claims on us, the old folks who cause this problem, not just the global warming problem, but all these problems. That's what I'd like to see.

Brandon Vaidyanathan

Okay, great. Thank you.

If you found this post valuable, please share it. Also please consider supporting this project as a paid subscriber to support the costs associated with this work. You'll receive early access to content and exclusive perks for members.